The first time I saw Jack Colwell perform was at the National Art School ball sometime around 2011 or 2012. There was a group of us. We’d been drinking at The Patterson. And when it was time to go the building owner wanted to come.

It was dark, and he was wearing sunglasses, and a pink dressing gown. He had a dart in one hand and a drink in the other. He didn’t have a ticket but it didn’t matter. “I got something better,” he said. “I got a ladder.”

So he carried the ladder to the National Art School and put it up against the walls. The National Art School used to be a prison, and we watched him climb over the wall and disappear. And there’s no point to any of this except: sometimes you have to break your way inside.

That night Jack played like a madman. And now, years later, on the eve of Jack’s final shows for sometime, we sit down and talk about the past at the Glengarry Castle Hotel in Redfern. We talk about ripped dresses and the clubs that are no longer here. We talk about acid baths and Tchaikovsky. We talk about the dark and light parts of our lives, and what it means to tell the stories we tell.

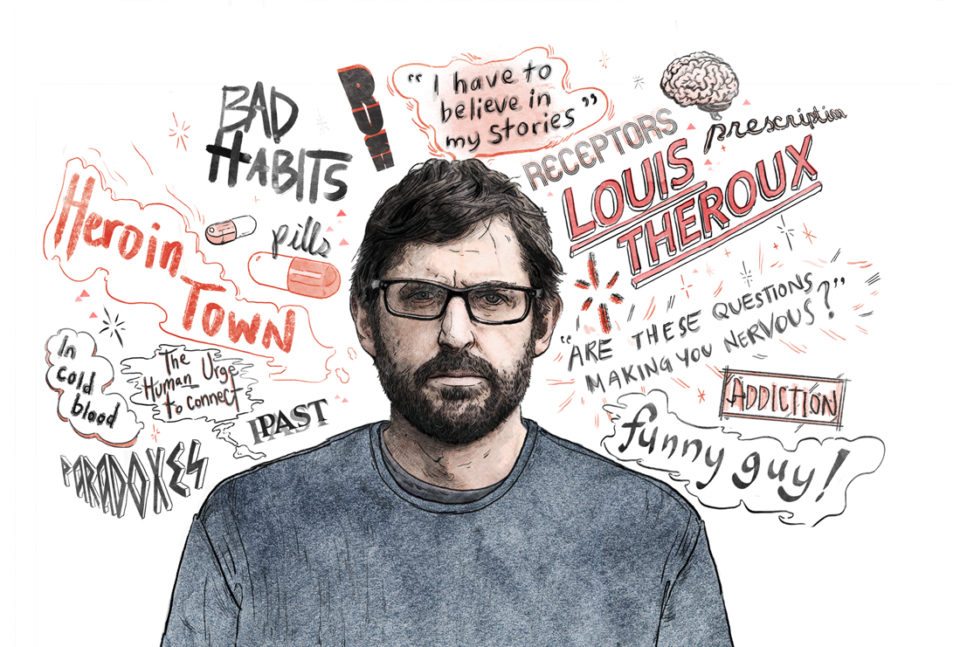

Jack Colwell. Image courtesy of Jack Colwell.

My favourite memory of you comes from 2011 or 2012. We were all ruined and partying at [painter] Lucy O’Doherty’s house for her birthday and it was 3am and you came downstairs in one of her vintage dresses and started dancing on the couch saying, “I’ve arrived, I’ve arrived.” Then the dress began to rip and you couldn’t get out of it. You apologised and told Lucy you were sorry. Do you remember that? Do you remember what happened to the dress?

I do remember, actually. We were at Lucy’s birthday. It was the end of a National Art School thing. I remember Lucy had this really beautiful dress, this sort of 1950s style blue or light blue dress with polka dots. I remember it exactly. And we were all really rat shit. It was probably one of the last great house parties that I ever went to. This really mercurial time of my life, like the party has now crystalised in amber. And we were actually dancing to Vengaboys and I remember jumping on that couch saying, “I’ve arrived, I’ve arrived.” I don’t think Lucy minded about her dress. Or she didn’t mind at the time. She never mentioned it later anyway. I don’t know. I felt like a lot of friendships were born and solidified in that evening and now that time has passed it’s a real symbol, for me, of youth and frivolity. Something we’re always chasing to get back.

Sort of like an old Sydney.

Definitely. Did Lucy mind about the dress? Did you ever hear?

I think she was fine.

Yeah, I think it was fine. I think she had a good time.

The best part was that you announced you had arrived. Of course, you’d arrived much earlier than that. Tell me about your childhood. Was it particularly musical?

Yeah it was. My mum was the driving force behind music. She was a piano teacher and a music teacher herself. And she pushed me into music from a young age, when I was five or six. I guess I really took to it.

I remember embarrassing things. I felt like the kid from those scenes in About a Boy where the boy sings Killing Me Softly with Toni Collette at the piano… my childhood was full of things like that. We sang some Roberta Flack but we mainly sang Peter, Paul and Mary or Bob Dylan songs at the piano or renditions of ‘Over the Rainbow’. My dad doesn’t play music but he calls himself: A Big Music Appreciator. He has every Rolling Stones coffee table book known to man and even some unofficial ones. So yeah, it was always there. Something I’ve noticed, I guess, is that I’m not a big music follower now. I just like to enjoy what I enjoy and a lot of that stuff comes from my childhood. Songs that I’ve grown with that have become part of my DNA.

Where would you say your influences come from?

For a really long time I was really folk-y. But everyone goes through that, I guess. I just loved listening to Joni Mitchell or Judee Sill or Peter, Paul and Mary. When I started learning bass guitar a teacher of mine got me really into 90s grunge and rock pop and that formed a part of my musical identity as well. I’m a bit stuck in the 90s at the moment. But maybe that’s not a bad thing. A lot of people our age grew up listening to that 90s stuff and, like Lucy’s party, I’ve just reached a really nostalgic part in my life where I’m thinking about older situations and that’s the music that brings up those memories for me.

Someone once told me the key to any relationship was for two people or things or ideas to meet and change at the same rate as one another – and to continue doing that until they died. Your time at NAS [National Art School] was nearly five years ago, and, at least for me, the city felt like a different city. I think this was pre-lockout but I could be wrong. What ties, if any, do you have to this city? How have they changed? Do you consider yourself a geocentric musician?

Yeah, it was pre-lockout. I don’t know if it’s just that I’m at a totally different stage of my life than when I knew you from my NAS days, but it does feel like a different city. A conversation that I seem to be having with lots of different people now is if I started being a musician now, if I was trying to gain some sort of popularity now… I’ve been asking myself what sort of path would I take and what would I do? I’m just not sure what the opportunities are in this city.

The Sydney I grew up in, there were a lot of places you could cut your teeth. There used to be 12 bands performing every Friday night at Mum at World Bar and that was genuinely really cool. Once upon a time The Jezebels played downstairs and Bridezilla and Papa vs Pretty played too. I mean The Jezebels just went onto support Midnight Oil and there was a time when that was an obtainable stepping stone for musicians staring out in this city. We had The Hopetoun. The scene was thriving and I felt really invested in a way that I’ve never felt about anything before. So many of my friendships were made during these times when I was 18 to 22. Watching bands or learning how to DJ upstairs at Spectrum or, you know, going to Vegas at Q Bar …

Or Phoenix Rising

I definitely went to Phoenix Rising a few times. I’m sure these things still exist in different forms but it just seems different now. But I guess music is different now. Something changed with the way people make music. A lot of it is done in people’s bedrooms and there’s a real introspection there.

I think there’s going to be a pushback soon, like anything when the tide goes too far one way the tide comes crashing back, and I think people are getting itchy. People want to see bands – but there’s not a lot of places you can do that. And that’s a big problem for Sydney. It has never affected Melbourne, but it has affected Sydney.

Having said that, I’m pretty Sydney based. I was born and raised in Sydney. A lot of the stories that I have in my songs are related to relationships I’ve had in Sydney. They’re about me and trying to make sense of all this mess, this Sydney mess. I guess my life is entwined in that.

It seems like if you’re an artist in Sydney you’re either one of two things. You’re either bank-rolled by your parents. Or you’re hustling hard and being productive because you literally can’t afford not to. I guess people can be mixtures of both too. I don’t know. I think there’s a brutal-ness to this city that pushes you because it’s hard to survive, both financially and emotionally. But that’s what I like about this city. It’s a scary city. It’ll fuck you up.

Totally.

Why haven’t you moved to Melbourne or Brisbane or Hobart? Have you heard people are calling Hobart “The Cold Ibiza”?

That’s funny. Well, I’ve always had something that’s tied me here. I mean, I thought about making the move to Melbourne two or three years ago when I was unsure about a relationship at the time. I thought I was going to form a new identity, or a better identity, maybe, you know, try it all over again, but something made me stay and there’s still parts of Sydney that I feel hopeful towards.

Like what?

Hmm. I guess it’s tricky when you’re actually pressed to think about it, isn’t it.

I look forward to the first swim of the season at Gordon’s Bay, or something. In terms of music, though, I think the scene has shifted. The Lansdowne has become a bit of a new space. And for a while there, before it became a mini-golf tournament, Newtown Social Club felt like a reinvigoration of the old days. I guess there are these little glimpses I’m holding on to. I’ve started to work with some of my musical idols in Sydney, and these new bonds, new friendships feel like a new vine or new leaf for me. It’s a great sense of solidarity in what has been a big period of transition.

Jack Colwell. Image courtesy of Jack Colwell.

I want to talk about transition and transformation. You’ve said your debut album

Well, we’re transforming all the time. I’m not the same person I was at Lucy O’Doherty’s party five years ago, and I’m not the same person who performed at the Enmore a few months ago, and I’m not the same person who released Don’t Cry Those Tears either.

I feel like we’re always changing and developing. It’s something that never stops. At the same time there’s a sense of purity and empathy I had as a child that I never want to go away. When I was younger I used to dress up in my mother’s dressing gown and find a reflective window and dance to Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake on vinyl. It was really private. No one really knew I was doing it. It was just something I did for myself. I guess I could have been playing computer games or reading books but I’d spend hours listening to those records and dancing. It’s something I still like to do as an adult. I don’t want to let go of that… that innocence.

The Swan Lake thing comes about because Tchaikovsky was actually a queer, or gay artist. He had a beard. He actually had a very full, nice beard, you can see from the photos, but he also had a wife who was quite knowingly his beard at the time. But he had quite a tragic ending. He bathed himself in acid and committed suicide because he couldn’t be who he truly wanted to be. [Editor’s note: Tchaikovsky reputedly drank unboiled water at a restaurant in St Petersburg during a cholera epidemic. The details of this, and whether or not he did it on purpose is contested.] And in a lot of his works there’s this real sense of grandeur that sounds inherently queer. There’s no kind of middle emotion or sound. It’s all painful and suffering or ecstatic and ecstasy.

That’s something I can relate to. I feel like I’m not very even keel on a good day. I’m kind of one or the other. And that’s the music I’m attracted to. And I think a lot of the stories he composed for the ballets, you know, only turning into a swan at night at the hands of a curse by a demon king, or the world of The Nut Cracker where he comes alive with the Rat King at night. They’re about these hidden worlds under darkness where you can truly only be yourself by the light of the moon away from others, and to me there’s a link with those stories in terms of queer narratives and coming out.

A lot of people who are queer do go through much of their lives in hiding and isolation. They live multiple identities to different people. Through acceptance you can merge these hats, you can erode the many different spliced versions of yourself. It’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, and something that’s awoken in the queer community with the marriage plebiscite.

For better or worse these stories of change or transformation will always be fascinating. And it is certainly something that fascinates me as an artist.

I remember seeing Anonhi several years ago at the Sydney Opera House. There was a Q&A and someone asked, “What do you do to take care of yourself?” Anonhi just looked at the person and said something like, “What don’t you understand? It’s not about me. None of this is about me. I have addictions. I am an unhealthy person. None of this is about me.” Can you relate to that statement? Who would you say your performance, your music, is for?

I began writing songs for myself as a form of catharsis. It was a way for me to document significant traumas in my life: my sexuality and growing up with domestic violence and sexual abuse. That’s why I wrote. That’s why I took to the piano initially. But I think after a period of time your writing transcends. It doesn’t belong to you anymore. Somebody else takes that work and it takes on a life of its own. You might write something that has one intention but that intention can be manipulated or changed or seen through a different lens or a different reading and that’s part of the beauty of making and releasing a work.

About a year or two ago, when all the safe schools stuff happened, I thought about where I was in my life. My position and sense of privilege and the very small platform that I have, I wanted to know what I could do to make a difference. I decided I could raise money for a mental health charity like a national network called QLife, and I raised a small amount through my music.

Two publications wrote about me and started calling me a role model. I guess that was their angle, but I found it a bit confronting to read. I mean, it’s 3pm in the afternoon and we’re sitting at the Glengarry pub, I don’t feel like the person they were writing about.

Lots of symbols and things about my life don’t mimic that. I can be on stage and be someone and then I can come off stage and go to the IGA to get a carton of milk. You know? It’s very funny in a way. It makes me uncomfortable. I think it’s a lot to be told. There are probably other people who are more deserving who have done more to earn those titles.

I try to be a good person but I also know there’s a darkness and a poison inside me. It’s hard to separate all these things. I feel like I’m always apologising or second-guessing myself. I don’t feel like this super-confident person who walks out on stage. I feel very unsure and worried about myself and I find it difficult to think of myself as a role model. I find it difficult to not see the parts of myself that I dislike. I don’t want to be a role model. I write for myself. I write about growing and changing. I’m a confessional singer-songwriter. The parts that are dark and the parts that are light and the narratives that I tell, I only hope that I tell those stories in a relatable way that people will want to be a part of that journey. Maybe it’s something they see in themselves too.

Jack Colwell end-of-year full band shows:

Sydney: Friday 15 December (9pm-11.59pm) – Waywards, Bank Hotel, 324 King St, Newtown / with Hollow States and Georgia June.

Melbourne: Sunday 17 December (7.30pm-11.59pm) – The Gasometer Upstairs, 484 Smith St, Collingwood / with Romy Vager and Rachel Maria Cox.