The photographer looks up to the sun. We’ve all assembled casually, as instructed, on the balcony for the photographer. The kids think it’s a great laugh but I’m wondering now if it’s a good idea. The journalist had been looking for families living in inner-city apartments. Looking down the lens, I no longer want to be in the Daily Telegraph’s Home supplement. What would Claud Hamilton, architect for our 1924 building Tennyson House, have made of ‘lifestyle choices’?

We’d bought the apartment on Farrell Avenue, Darlinghurst, at the end of a frustrating search. It was a nice old building but the large balcony that doubled as a living space had clinched it. We imagined a short turnaround while we did it up and flicked it, Sydney-style. That was almost twenty years ago, before kids.

Monika, the building oracle from flat eight, had lived there since the seventies. She and her husband, both Polish émigrés, had met on the Snowy Mountains scheme and she’d stayed on in the building after he’d died. Monika had lived through the squatter’s fire that partially gutted the building in 1987. She assured us that, although we might think gentrification was happening, we were wrong.

“Too much noise, too much druggos, too much prostitutes, it will never change.”

The screams we’d hear at night backed up her claims. Apart from the needles in the garden, we came across a sex worker servicing her client in the garbage room and we began to reconsider our options.

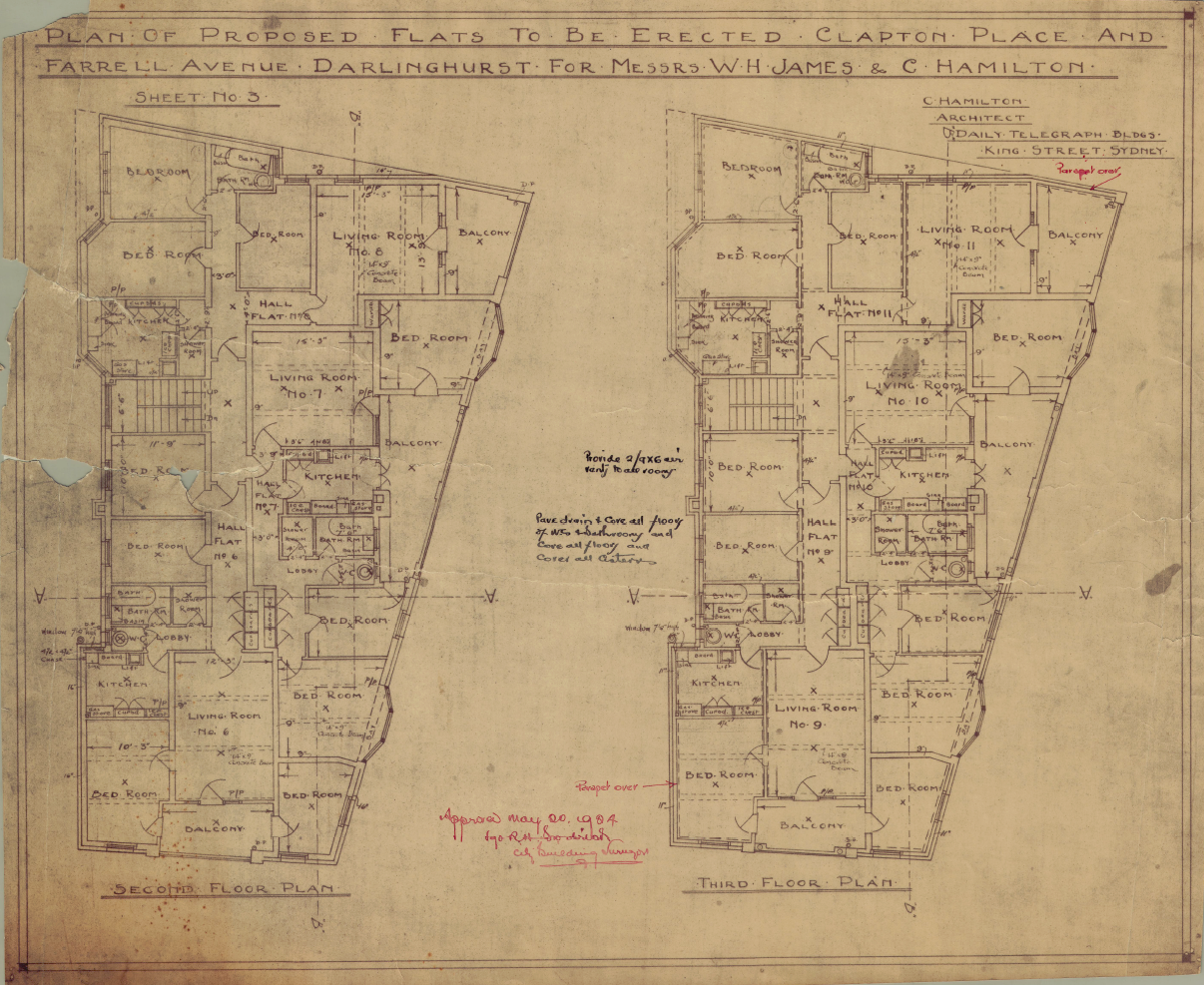

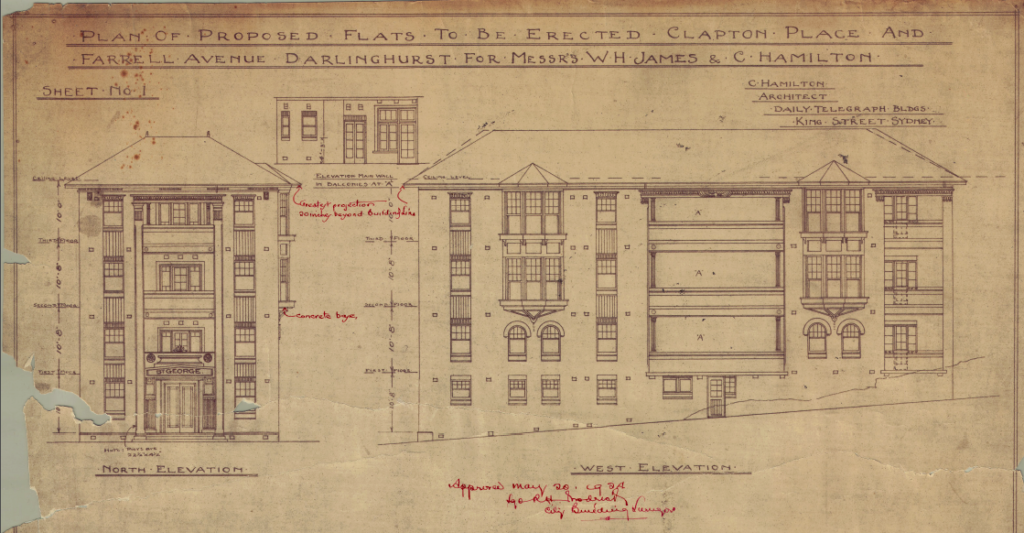

Tennyson House plans, 1 Farrell Avenue, Darlinghurst. Prepared by Claude Hamilton, 1924. Credit: City of Sydney Council Archives

One summer evening, excited chattering from the street drowns out the bats feasting in the tree. From the balcony I see a small crowd gathered on the footpath, watching a performance on our entry porch. It’s a walking tour tracing literary characters of the Cross. The actor is playing Dulcie Deamer, novelist from the 1920s and 30s, known as ‘The Queen of Bohemia’. I research and find that Deamer was known not only for dancing on tables in leopard skin dresses with Chips Rafferty, but that she’d lived in the flat below ours for many years.

It’s the same flat where the young Portuguese couple now hold their folk music sing-along evenings. I find a 1940s photo of Dulcie posing on our front porch and think of her when I photograph our eldest, and then our youngest boy’s first days of school on the same porch steps.

Wolfgang sits on those porch steps on sunny afternoons while a constant stream of strangers drop by to see him. When I notice the foil wrappers that Wolfgang passes subtly to his visitors I begin to understand his popularity. One Sunday I’m drilling into our living room wall to hang a mirror. The noise can be heard right throughout the building into the street, a fact Wolfgang is quick to remind me of when he sees me. He tells me he was partying at Sleaze Ball until ten o’clock that morning, and he is now going to have to kill me. It’s said with a smile, but I cease my drilling plans for the rest of the day anyway.

Years go by and we’ve become stuck in this building, stuck in this place. We try to move but roots have been laid: schools, jobs, and friendships. And there’s something else, a pull that holds us. I get involved with the body corporate organising maintenance works and we obtain the original building plans from council archives. The architect’s name on the drawings is C. Hamilton of the Daily Telegraph building in King Street. Who was C. Hamilton? I research further and through the Australian Institute of Architects I discover gold.

Claud Hamilton, born in New Zealand in 1892, had migrated in 1913 and established his architectural practice soon after. Throughout the 1920s he built residential flat buildings in the Kings Cross area, designed in a restrained Federation Arts and Crafts manner. Hamilton designed at least fifteen buildings in the area with Byron Hall on Macleay Street being his finest. However it’s the revelation of the ways in which his buildings have overlapped with my life that intrigue me.

To my surprise I learn that Hamilton had designed Kaloola in St Neot Avenue Potts Point in 1927. We had lived in Kaloola prior to Tennyson House. The bay window of our living room there had glimpses of Garden Island and we’d hear the early morning sirens waking up the sailors. Above us lived an infamous local photographer who teetered into restaurants offering diners paid photos from her instamatic camera. Her beehive wig and makeup were always out of alignment, and every night we’d hear her heels clacking home up the terrazzo stairs after midnight.

Rory lived in an apartment near ours and had been romantically jilted one too many times. The building’s light well provided light and ventilation to the internal bedrooms but it would also reverberate noise up and down its height. Late at night we’d hear the desperately slurred wails of Rory into the darkness, “Nobody loves Rory. Rory loves everyone but nobody loves Rory”.

The Institute of Architects’ heritage report describes Kaloola’s features. They include recessed balconies, corbelled brackets, and a central keystone incorporated in a building frieze. There is no mention of Rory or the asymmetrical photographer. Hamilton had designed Wirringula, the skinny building opposite that was featured in the film, ‘Dating The Enemy’. We’d looked at an apartment there but it was too expensive, not helped by its celebrity status.

I’ve taken to losing myself in family history research and obtain the marriage certificate of my Dad’s parents. My grandmother often spoke of the fun she’d had as a young woman living in the Cross. In her nineties I visit her tucked away in the War Vets home at Collaroy Plateau, and try to imagine this frail old woman in more vibrant times.

My grandparents, Marion and Max had married at St Johns Darlinghurst in 1935. The same St Johns whose grounds I walk through on the way to Bar Coluzzi each morning. Opposite the church is the St Johns Flats building from 1916, one of Hamilton’s first projects. To me it’s an old-fashioned banger compared to his later, more refined buildings. I share these thoughts with my wife and she tells me I’m getting boring.

I’m looking for Hamilton everywhere now, mildly obsessed. Adjoining St Johns is the Savoy apartments on Hardie Street. It had once employed a concierge at the entrance and a dining room on the sixth floor. Hamilton had been commissioned for the design in 1918. We’d been to a party there once and I’d admired the owner’s artworks and immaculate parquetry floors. On the way home we’d argued about our own inferior home furnishings, which were more Ikea in their flavour.

The marriage certificate also indicates that at the time of their wedding, Max lived at 69 Darlinghurst Road. I go in search of this address and find myself standing on the footpath next to Porky’s, peering in through the glazed doors of The Normandy flats.

I don’t know if I’m more excited to make this connection with my unknown grandfather or to learn that Hamilton had also designed The Normandy in 1926. The coincidence is strong but the link with my grandfather is compelling. I’m wondering about his life beyond these doors, desperate for clues. Was he one of the poet Kenneth Slessor’s ‘gents’ cooking ‘his pound of mutton chops’ (‘Kings Cross’)? Would he and Hamilton have crossed paths?

From my family research I learn that Max Ashton, born 1894, had been a dock clerk in London before serving in the Great War. He had left England in 1924 for Sydney, working as a radio journalist. When he met my grandmother she was sixteen years younger and living at 29 Hughes Street Potts Point. It’s behind Byron Hall and now part of the Wayside Chapel, where my parents were later married. Marion was to outlive Max by half a century but would always refer back to him with reverence. In her later, less coherent years she would confuse my Dad for Max.

But I haven’t finished with Hamilton yet. He designed the Victoria Garages on Victoria Street near Messina, with a substantial residence above. Today the building houses a bottle-shop with a French wine selection at the front. I head past these to the bargain bins that house the lesser-known domestic brands.

In 1927, Hamilton was designing Kaloola in sleepy Sydney, while Corbusier and co were a world away reinventing modern architecture. The white walls, flat roofs and clean lines of the International Style would become the main game for much of the century. It would leave little room for Hamilton’s Arts and Crafts motifs.

Claud Hamilton died in 1943 leaving a wife and children. It was a year after Max Ashton had died, leaving his wife and my dad as a one year old. The two men, similar ages, had lived in the same area at the same time. I search for more information but the trail is cold.