Dr. Cameron Webb stands in the thick mangroves of Olympic Park, holding a mosquito trap to his ear. “There are probably ten different species of mosquito in here,” says the University of Sydney Medical Entomologist, adding that there are 300 different types in Australia and 60 in the greater Sydney area alone. “Listen,” he says, proffering the trap so that the sound of the tiny creatures is audible. Webb explains that they are singing love songs to attract each other.

For some mosquitoes, “the male and female sing to each other in harmonies with their wing beat frequencies before they mate,” Webb says. However, even though mosquitoes use sound in this way, female mosquitoes aren’t always responsive to it. “That’s why your smartphone app that purports to using sound [by emitting a high-pitched frequency to supposedly mimic predators] doesn’t work.”

Webb has been studying these insects for over two decades, and considers them seriously misunderstood. “Mosquitoes aren’t a flying dirty syringe that transfer droplets of blood,” he says, describing them instead as “fascinating creatures who are sometimes incredibly beautiful”.

He argues that “scientists are really good at working out how to kill mosquitoes,” but not enough research has been done in other areas. Webb’s love for the insect has led him and his team to discover a secret inside the typically unlovable bugs – they could hold the key to fighting some of the diseases they threaten to infect us with.

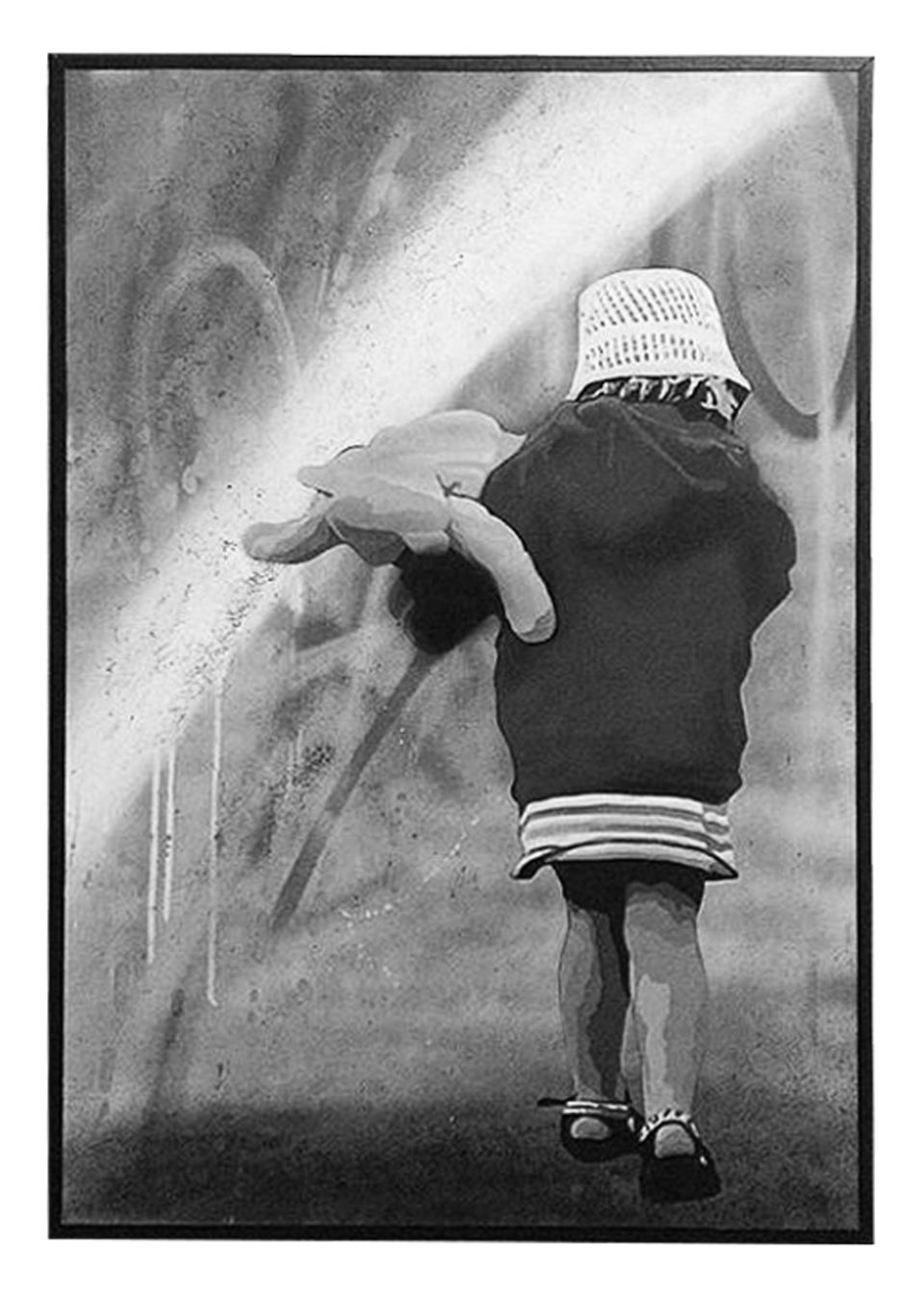

Dr. Webb. Photography by Nick Gascoine

In 2007 Webb and his team “discovered a virus in local mosquitoes called the Parramatta River virus”. He stresses they are in the early stages of research, before he explains that this virus “doesn’t make humans sick. But when mosquitoes are infected with it, we believe it might block their ability to transmit other viruses to humans, almost like a vaccine.”

This would potentially solve the health risks mosquitoes carry, such as the deadly viruses of dengue and malaria. It could also mean an answer to the severely debilitating Ross River virus, of which roughly 5,000 cases are reported annually in Australia.

Yet due to climate change, the mosquito itself may be threatened. “People think that climate change will only mean more mosquitoes, but… when it comes to sea level rise, we might lose [them].” The insects are specific to the habitats they breed in; areas ranging from back yards to storm water drains, and wetlands. Mangroves and saltwater marshes are those that will be most affected by rising tides. Another factor is urbanisation. “We’ve built right up to the edge of our waterways with hard physical structures and these habitats can’t find somewhere else to be established.”

Webb considers time is of the essence. If mosquitoes disappear much else may change. He explains that a range of animals eat the insect including reptiles, small birds and mammals such as the Microbat, “a super cute little animal that eats insects”. Although Webb says that the mosquito is not the primary food source for most of these animals, they are eating enough to conclude “they probably play an important part during some component of their life cycle.” If mosquito numbers plummet, these animals will also suffer.

Although Webb has been bitten numerous times over the years, he considers himself lucky – and not just because he has never been infected with a mosquito borne virus. His love for the summer pest remains intact. Few people are aware that it is only ever the female mosquito that transmits disease. “Only the female bites,” Webb explains, as they need the nutrients found in blood to develop their eggs.

“I’ve never met someone who hasn’t got a question or comment to make about mosquitoes,” he says. “I’m never short of a conversation.”