It’s hard to make sense of war – its chaos. Is that why it’s hard to make sense of War Machine, an American internet film by an Australian director about foreign forces in Afghanistan in 2009, whose narrator is only revealed an hour in and then largely disappears?

Brad Pitt’s General Glen McMahon is the Yankee sent to bring the war in Afghanistan to a close. He refuses to believe it’s unwinnable and remains steadfast in his mission to liberate the hell out of the country, despite the advice from his press advisor (Topher Grace), protestations from foreign politicians (namely Tilda Swinton) and the increasing eccentricity of Afghan President Hamid Karzai (Ben Kingsley).

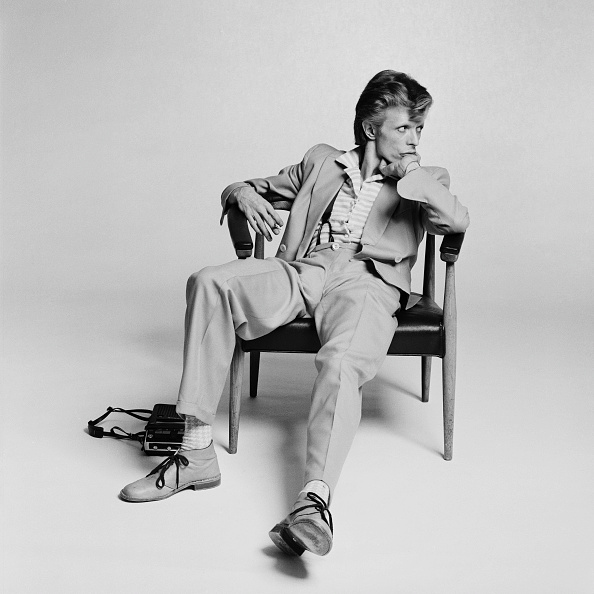

McMahon is the type of strange creation familiar to us from Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22 and Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove, two classics of anti-war satire. Pitt summons a highly stylised performance, right brow cocked and elbows angled like a GI Joe, popping out from his sand-soft khaki surroundings like a two-dimensional paper cutout.

There are moments when he bursts behind the realm of cartoon: as the film progresses, Pitt creates real empathy, communicating that the failure of the war will be the failure of the project of McMahon’s life.

The problem with War Machine isn’t Pitt, it’s elsewhere. Dr Strangelove had the kind of heightened dramatic tone that created a structure to let us understand the actors’ farcically exaggerated performances on their own weird terms. But watching War Machine, you begin to suspect that Australian writer-director David Michôd, of Animal Kingdom notoriety, has been whisked away to Hollywood before he can fully develop his own fingerprints as a storyteller, his own approach. Like the war itself, the film is all over the place, with scenes darting between action filmmaking, comedy and drama.

Netflix provided him with a rumoured $60million to adapt Michael Hasting’s book The Operator, but the newest catch-22 for people like Michôd is that politics now satirises itself without the interventions of political storytellers and comedians.