I don’t like the Beach Boys and I don’t surf. Yet my heart feels raw as dirty beef when it slides back to the moment in 1977 when Dennis Wilson, the band’s husky-voiced, boozehound drummer, let rip with: “Is it any wonder/The Pacific Ocean is blue?”

Dennis’ blue I know. His blue I can feel even living far from the sea.

My home is near wild rivers, and rivers fare better than oceans on his stormy solo debut, Pacific Ocean Blue.

Dennis, the only Beach Boy that surfed, opens the album with ‘River Song’. He sings of fleeing the grubby cage of city life to an ecstatic river-world, revelling in its power and sensation, with “water running through my knees”.

Dennis, yes, fucking yes, and I can’t stop this song running through me.

It fades when I head upstream from home to float under fallen trees and over eels and platypuses and rock. At that time, where I am is all I am.

But later, to forage for money by teaching university students in Sydney, I’ll drive, still glowing from the mountain water, towards my Inner West digs, ‘River Song’ turning bittersweet on my car stereo as the high finally dies in traffic and fumes.

You know it, Dennis. In ‘River Song’ you roar about LA being, “So crowded I can hardly breathe.” Sydney, too, brother. And you sing how cities limit the vision – yes again; they shove our heads under so many influences that we drown: the scungy flesh-shell that’s left getting channelled down this or that scum-tube to emerge like fucking zombies aping the masters of urbanity and its all-important fads and moments.

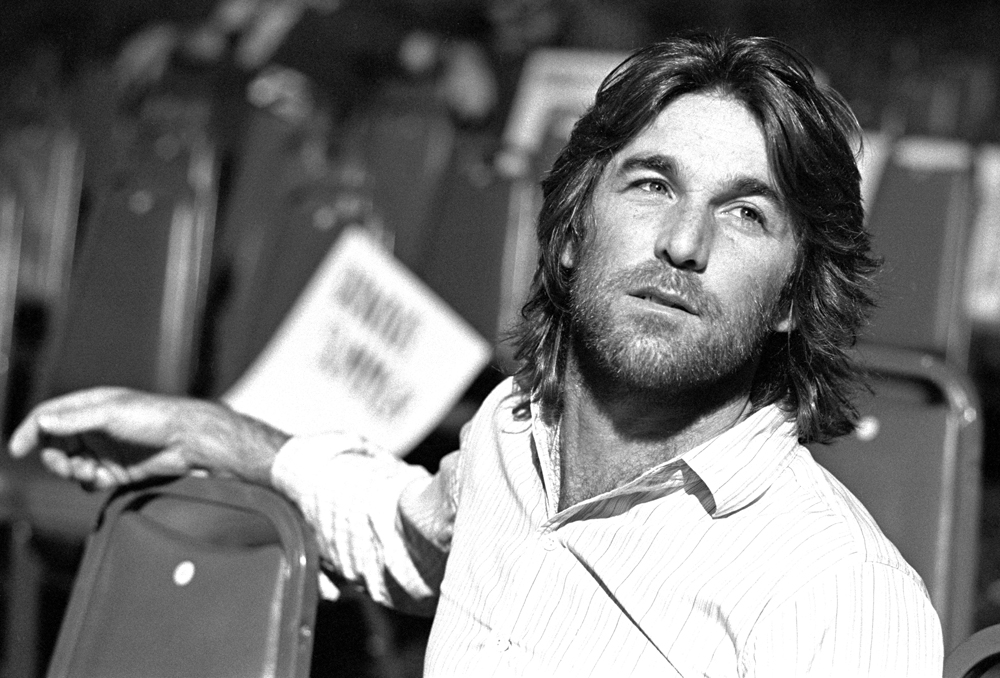

Circa 1971: Photo of Dennis Wilson for the film Two Lane Blacktop. Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Pacific Ocean Blue tracks a similar flow. Dennis takes the river straight down to America’s West Coast, where, “We live on the edge of a body of water/Warmed by the blood of cold hearted slaughter.”

Back in 1968 Dennis had a diabolical master for one long, ruinous moment: a moment still rippling fifteen years on when he drowned in Santa Monica Bay while drunk-diving for the totems of one of his many ruined marriages.

That terrible, rippling, cosmos-ripping moment in ‘68 was Dennis’ collision with psychedelic Nazi-god Charles Manson. The Beach Boys had made Dennis unbelievably loaded. When Charlie’s advance guard of honey-trappers spread their diseased thighs for the dissolute star Dennis gave them keys to his house, his cars, his world. “I live with 17 girls,” Dennis told a newspaper. And in this orgy of everything was Charlie, a crazy pimp wizard whispering of freedom and the soul while craving a music deal.

By all accounts Charlie had a certain something. Something there. A song sketch of his called ‘Cease to Exist’ was developed by Dennis into a 1968 Beach Boys B-side ‘Never Learn Not To Love’, but Dennis didn’t see reason to credit the pushy little ex-con. Charlie threatened him – and his children; Dennis, free spirited and reckless, beat him up. But you can’t just bash Charlie and then sleep well. Dennis fled his Sunset Boulevard home and avoided the Mansons completely. “You got to run away/You got to run away,” he says over and over on ‘River Song’.

Later, when the Manson Family’s LSD killing season had exploded in the blood calligraphy of ‘Helter Skelter’, Charlie emerged again, this time from the desert in handcuffs. His girls followed him into court with X’s carved into their smiling faces.

Dennis drank harder than ever, living in morbid fear and, some thought, guilt for helping open the L.A. scene to Charlie’s insanity. Some likewise thought the killings were borne of a psychotic jealousy. Charlie could have been, should have been, someone like Dennis. When that didn’t happen he found another outlet for his talents.

As the Beach Boys mutated into their own covers act, Dennis seemed more and more like his gifted brother Brian. He’d always measured Brian with love as “an inspiration not an influence”. Pacific Ocean Blue pays wild tribute to that, its mystique enhanced by a feeling this was the album the Beach Boys should have made: great, relevant, tormented rock music in 1977. Dennis had caught what was happening: “the white punks play tonight” (‘Friday Night’). He’d already been crushed by the corporate mediocrity of the Beach Boys, offended by what was being done in their name and to their greater musical heritage, which he’d seen as “spiritual” and “beautiful”. Pacific Ocean Blue’s rich dark sound carried his deeper calling.

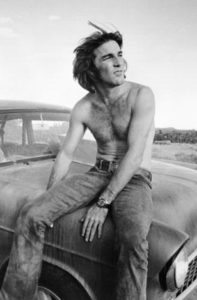

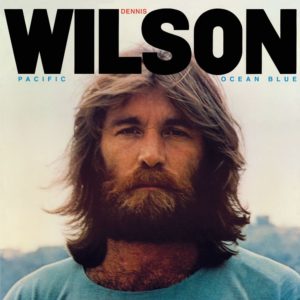

Dennis Wilson ‘Pacific Ocean Blue’

But over time Dennis degenerated completely, spoiling friendships and love, hurling their trinkets and reminders – and finally himself – into Santa Monica Bay after months of homelessness, benders, and brawls where he took a pounding.

Well before his terminal swan dive of a few days after Christmas 1983, Dennis – incidentally, the songwriter (with Billy Preston) of Joe Cocker’s hit, ‘You Are So Beautiful’ – had recorded not only Pacific Ocean Blue but additional fragments that would be assembled and released posthumously in 2008 as Bambu. There’s so much expressed in his voice alone: a throaty, lived in, wide open, doomed, great, husky allness.

The track from Bambu that I can’t stop listening to is ‘Album Tag Song’. It has a looping, fatalistic, falsetto laugh over piano with a few lyrics thrown in, including “Better times ahead”, that would have made Dante bliss-out while riding Dennis’ sad laugh down to the Ninth Circle of Hell.

Dennis, your 39-year-old corpse was burned and scattered offshore and you can’t hear me any more. But I wish you could know that I listen to your madness all the time. All the fucking time.

‘Ghosts in the Machine’ is a column dealing with the unique and intimate ways that artists become iconic figures in our life. We are open to short submissions, preferably 300-400 words.