“Here’s to the hearts and the hands of the men that come with the dust and are gone with the wind.”

– ‘Song to Woody’, Bob Dylan

By the time Bob Dylan rises from his piano to take a final bow with His Band, the night feels less like a rock ‘n’roll show and more like having entered a grand story of some kind. Dylan’s jangling walk across the stage meanwhile betrays a glimpse of his very real mortality at 77 years-of-age, giving credence to reports he can no longer sustain playing the guitar due to severe arthritis (a rumour he denies). I wonder if the source of this dangled stride might date back to his break-neck motorcycle accident in Woodstock in 1966, not to mention a case of hard living and life on the road that would have killed most anyone by now? Reports, rumours, denials… for someone so famous Dylan has about as much substance as smoke in the wind. In many ways, his songs are more real than him. Yet here he is anyway.

Inherent in his performance is an intense feeling of time. Not ‘time’ as something nostalgic or revived, but a force flowing, glittering and unfixed. His songs and their influences nod to a history that is lived, a thing within rather than behind us.

The mood is enhanced by the appearance of his band, all dark suited and sparkling lapels like some gunslinger cabaret act, the stage lit mostly in yellows and shadows with giant klieg lights hanging precariously above as if on some Hollywood set. The ultimate atmosphere, the illusion in this old art deco theatre, is of a barn dance and sawdust on the floor around us.

Tonight, through Dylan, we keep company with Cole Porter, Hank Williams and Muddy Waters, with Jack Kerouac and Arthur Rimbaud, with Greenwich Village in the 1960s and an American West that belongs in dime novels, with cold North American mining towns and railway iron in the soul, with love and contempt and God-fearing and faithlessness, as well as gnarly doses of paradoxical humour and misogyny that remind us of Dylan’s darkness and unpleasantness as much as his genius. The Shakespeare of our age, he breathes it all in and he breathes it out right in front of us.

I can’t escape the feeling that even if eight of his lives have been spent, Bob Dylan has at least one more left to surprise us with. And that something wonderful is brewing within him: a sequel to his memoir Chronicles: Volume One, a bootleg spin-off of Blood on the Tracks and Desire, a longed-for album of fresh original material and a whole new creative era. That’s very exciting to contemplate. Dylan isn’t just ‘back’, he’s going somewhere.

The mystery of this evening is how he got to be this mythical – and yet so human again? It’s as if Dylan has fought his way back into being here and is saying a strange thank you to a dream that almost destroyed him, a dream that started way back in the 1950s when a young Robert Allen Zimmerman fell in love with literature and music and began reinventing himself as someone he’d eventually call ‘Bob Dylan’.

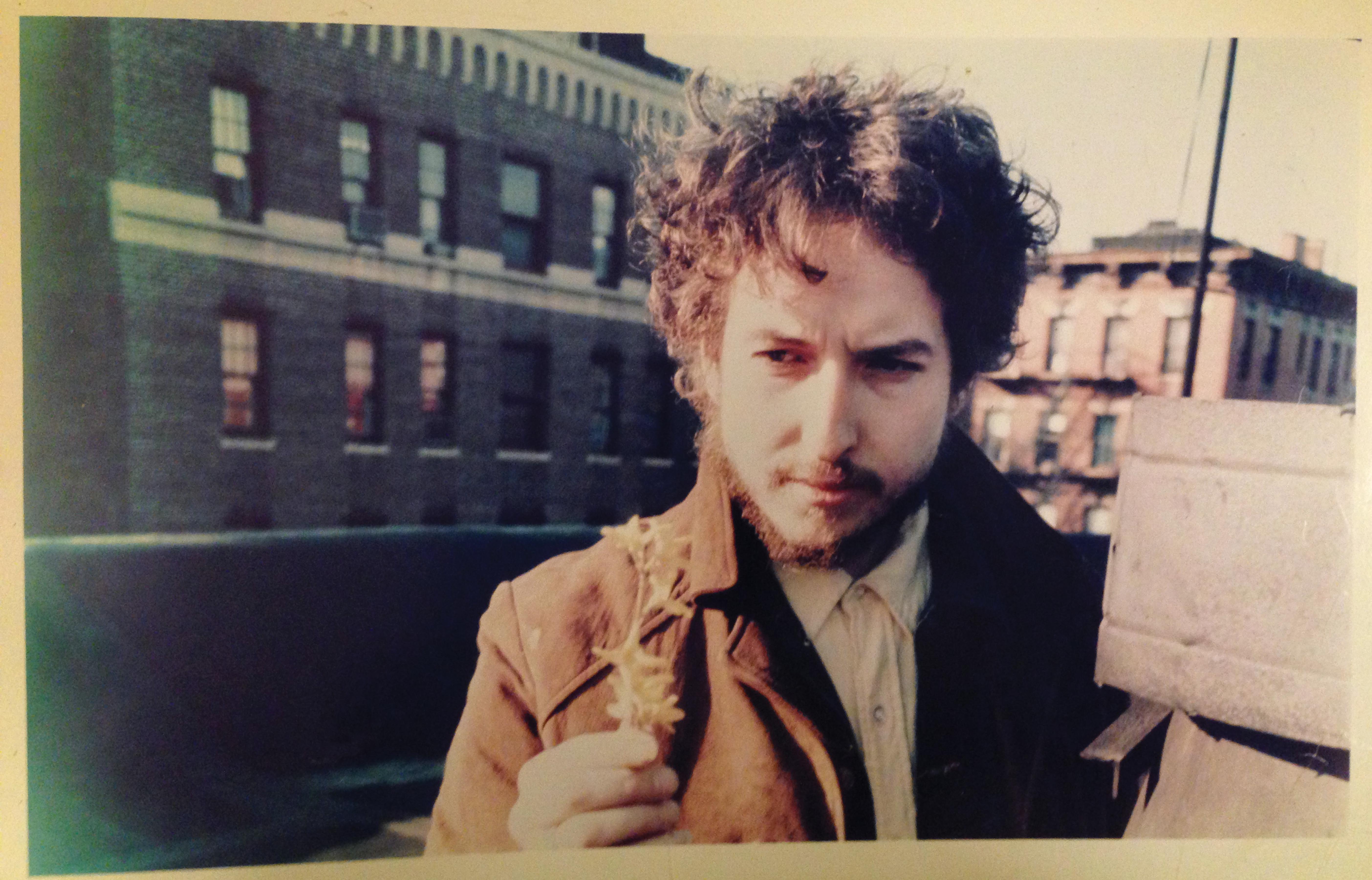

Bob Dylan, Tempest era, 2012.

The night begins with black-hatted guitarist Stuart Kimball playing disparate notes that seem to have been sheared from ‘Waltzing Matilda’ without ever fully evolving into that melancholy song. There’s no big overture, just the hum and clatter of the band picking up instruments and taking their places as we recognise fragments of Australia’s unofficial national anthem. Be it root or branch, this musical trace is in keeping with the entire evening as zeitgeist melodies surge forward and fall back again into the band’s beautiful noise. Post modernists might call this type of thing ‘quotation’; hip hop artists could compare it to the practice of ‘sampling’. In the blues, country and jazzy popular standards that flow into Dylan’s ‘50s tilted rock ‘n’ roll it feels like nothing less than the irruption of his youth, a calling he once heard and depends on again. Things aren’t over. They are just beginning. Maybe it has always been this way. The old man is just a boy dreaming he is an old man. And the old man is smiling.

The band is already getting into a groove when Dylan grabs his seat at the grand piano. He’s still easily identified by his trademark birds-nest of hair, though these days it’s a little less the electric halo that so enchanted Jimi Hendrix and more some half-crazy composer. Maybe Charlie Sexton was on to something decades ago when he first met Dylan and was reminded of “an old owl”: a creature one associates with wisdom, magic and predation.

For the rest of the evening Dylan will alternately sit and stand at the piano, playing in a way that suggests Little Richard’s rhythmic force and Fats Waller’s joyful feeling in composing the popular jazz standards of yore. In other words, you tend to hear the 1950s and 1920s in Dylan’s playing, and while he is no Mozart on the keys he totally drives the band and has a potent melodic touch that mutates – at will and almost carelessly – between those decades and every other era between. Texan swing, hard edged Chess Records blues, ragtime popular ballads, juvenile delinquent collar-up ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll… Dylan might just as easily be touching the dial of some cosmic radio as running his fingers over the ivories. At times, it feels as if the band is mashing all those sounds together in a single tune, trying to catch up with whatever world Dylan might be time-tunnelling himself into.

‘Things Have Changed’ and ‘It Ain’t Me, Babe’ open the set. The band runs into them like a misfiring hot-rod, with an echoing and harsh sound that sees them struggling to find any instrumental balance at all. It’s just too freaking loud and clashing. The line between racing machine and car-crash is worrisome after so many reviews that have told us how great Dylan is again. Are we to be denied? Then ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ kicks in and the band lock on to a sound that is so tough and mean the guitar ghost of Link Wray might be looking over their shoulder nodding at the rock ‘n’ roll rumble below.

The tempo drops back on ‘Simple Twist of Fate’, its opening phrased as if Dylan were crooning it in the early twentieth century. “They sat together in the park as the evening sky grew dark,” comes over as laughably corny, with Dylan’s quavering voice creating the impression that even he is having a joke with himself. But as the song unfolds there’s a sense it has become kinder and more forgiving rather than tragic, that it is now about the act of letting go and accepting an experience of love instead of being wounded by it. For a lot of people, it’s not till Dylan actually says the words “simple twist of fate” that any recognition and then applause arrives. ‘Tangled Up in Blue’ gets a similarly fresh treatment and an oh-so-that’s-what-it-is response – once he recites the title emphatically into the microphone like he is laying down a vital clue. To be honest, I much prefer the original arrangements, but these new treatments make me hear the songs afresh and rethink my listening of them. Like I might relearn them, or that maybe he has and this is the most important thing of all. ‘Maybe’. I seem to reach for that word a lot to understand tonight.

‘Early Roman Kings’ stomps like the Muddy Waters pumper that it is. ‘Love Sick’ sounds menacing, a knife in the heart, a matter of sexual addiction he can’t resolve. ‘Visions of Johanna’ is neither sweet nor sour, yet entirely redefined. At times now, writing about the night, I lose track of myself and feel unsure of what happened as I entered the landscape of the songs. ‘Visions of Johanna’ has a sound you could only call golden. ‘Trying to Get to Heaven’ has a similar beauty, an ache about wanting to have a soul and not making it, or not seeing it understood. But what kind of words are they… ‘soul’, ‘golden’, ‘lost’?

Bob Dylan live on stage. 1966. Image by D.A. Pennebaker.

It must be quite some feat to pull together a band that can grasp such a broad and deep musical vocabulary. As skilled as they are, the emphasis is on feel more than perfection. I had heard by the turn of this century that Dylan’s road band was required to know over 200 songs by heart. And be ready not only to play them, but also bring on any change of tempo and stylistic treatment as per Dylan’s mood. No surprise that this could also lead to some stress and strain. These days it’s common knowledge Dylan plays to a much more narrow and defined set list, something that must release his band into the pleasure of playing.

Even so, about a quarter of the songs seem to end on nothing more than Dylan’s nod or a glance from his eyes – when the band falls into line accordingly. The relationship between Dylan and bassist Tony Garnier seems particularly close, while Charlie Sexton appears to work as hard as he can to please the master, moving from Les Paul jazz notes to hard cowboy blues, shaking out a little stiffness in his hand now and again. Sexton and fellow guitarist Stuart Kimball work like two men sawing down a big tree, cross-cutting and overlapping their energies. Maybe there’s a shared Scotty Moore influence on their playing, tough but modest, serving the song every time, working as one. Donny Heron on pedal steel, mandolin and violin, brings in those Texan swing and timeless folk flavours. George Receli slips in a ‘Wipeout’ drum solo during ‘Thunder on the Mountain’ – much to Dylan’s pleasure – but for the most part he manages to be percussive and colourful without marring the rhythm with anything too busy.

Overall there is a curious individuality to all of the band; a cultivated edge of anarchy where they lose unity and begin to make a racket that elasticizes and comes back together into something fine. Most beautiful of all is Dylan’s harmonica playing, so rich and honeyed its almost enough to make you cry.

As for Dylan’s voice, it’s so cracked and raspy it makes Tom Waits sound like a blue-eyed soprano. A shotgun blast into an ashtray would have more polish and consistency. But any idea that Dylan is a bad singer, or that in last decade he has been a far greater songwriter (at least in so far as a late masterpiece like Tempest might prove) than a vocalist (all those albums paying tribute to Sinatra et al and Dylan’s own abilities at the old soft-shoe shuffle) is just plain wrong. I’ve sometimes wondered about the camaraderie he documented in his memoir Chronicles between himself and Tiny Tim as mutually struggling artists in early 1960s New York. We place so much emphasis on Dylan as a songwriter it is all too easy to forget his innovative force as a vocal stylist, paving the way for singers like Neil Young and Tom Waits. Frank Sinatra was certainly a fan, recognising in Dylan a like-minded cinematic vocalist acting out the character of the song.

Working within his own peculiar limits, exalting in a life-long brilliance at phrasing and undeniable feeling for song narrative, Dylan naturally touches the words that he wants to touch and redefines their emphasis with ease and intimacy tonight. He’s not just a good singer, he’s a great singer – reawakening lost phrases, regenerating your formerly fixed sense of what a song was and how you heard it. I’m guessing in his crusty tributes to the Great American Song Book in this last decade and in his own song-writing repertoire he is smart enough to write his voice into the equation, making the most of his aging and the ages he has lived through. As for the musical arrangements now that are so radical certain songs appear to have developed entirely new melodies, it could be part of a vocal need as much as any desire to shake out a familiarity that may have made us forget what else the songs contained.

That’s not to say these new interpretations and musical shifts of gear are always an improvement. Or that Dylan was not always this way inclined, as any in-depth listening to the riches of his Bootleg series will reveal.

But after decades of sporadic performances that wrestled against what seemed to be a spiritual torpor and a passive-aggression towards his audiences and even his own songs, such changes are the sign of a Dylan who is most definitely back in the world. When he sings in ‘Pay in Blood’ and “I pay in blood but not my own” I don’t really believe him, powerful as it sounds. It’s tough guy acting, and the guy I see on stage – mean and nasty as he can be – is more of a giver than a taker. When I stumble out of the Enmore Theatre as surely as I might have finished a wild night at Al Swearengen’s saloon in Deadwood, everyone around me is energised, delighted and aflame with this gift. It was legendary.

Leaving the Enmore Theatre. 2018. Photography by Samantha Hutchison.