They came and swore an oath to tell the truth, a parade of “poofter bashers”, the likes of which had never been witnessed in an Australian courtroom.

“I was the youngest one,” said a Narrabeen man. “I was the sheep; just the follower.”

He was 17 in 1987 when he went gay-bashing with his mates at Narrabeen, St Leonards Park, Reef Beach and – he can’t be sure but maybe – Moore Park in Surry Hills. He was by no means the youngest of the teenage thugs who attacked homosexual men and who, now middle-aged, gave evidence in procession last month at Glebe Coroner’s Court.

There was the 45-year-old who took off his shirt in the witness box to display the tattoo he got as a teenager. He still bears it on his upper right arm: The Grim Reaper, the scythe-wielding personification of death. He said he was 14 when he and his crew from Narrabeen went to Moore Park, also in 1987, to “roll a poof”.

Then there was the witness who had killed a cat and put its head in the freezer. One of his old mates, who testified, had heard that he’d put his mother’s budgie in the microwave. A secret informant came forward to say the cat killer and a Narrabeen skinhead boasted to him, when he was young, that they bashed an “American faggot” who they found naked and masturbating around Manly or North Head. It was a Friday night in mid-December 1988.

Scott Johnson was an American homosexual. Spear fishermen found his naked body on a Saturday morning – December 10, 1988 – at the base of a 60-metre cliff at North Head, near Manly. More than 28 years later, his death is the subject of an extraordinary third inquest. Only the death of Azaria Chamberlain at Uluru has been the subject of more coronial attention in Australia.

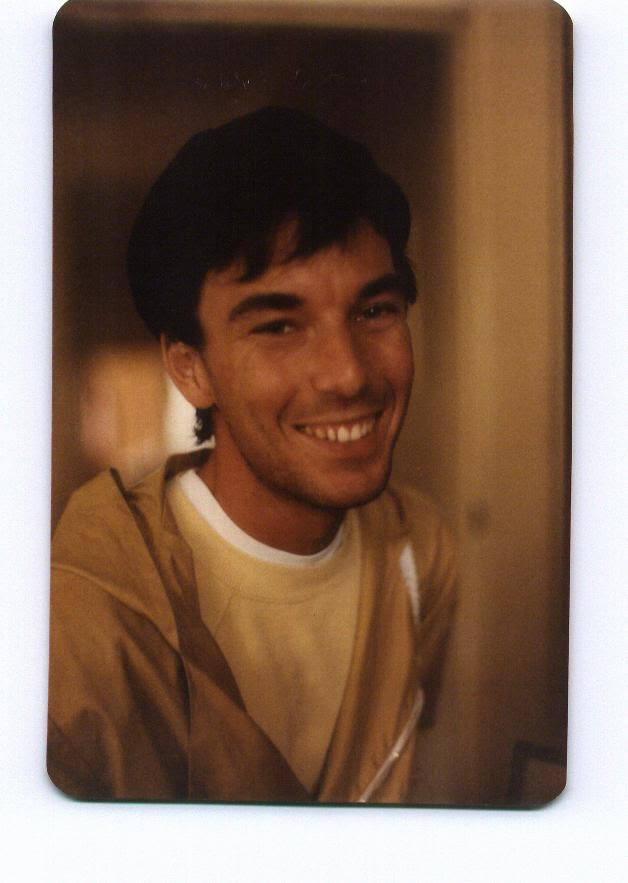

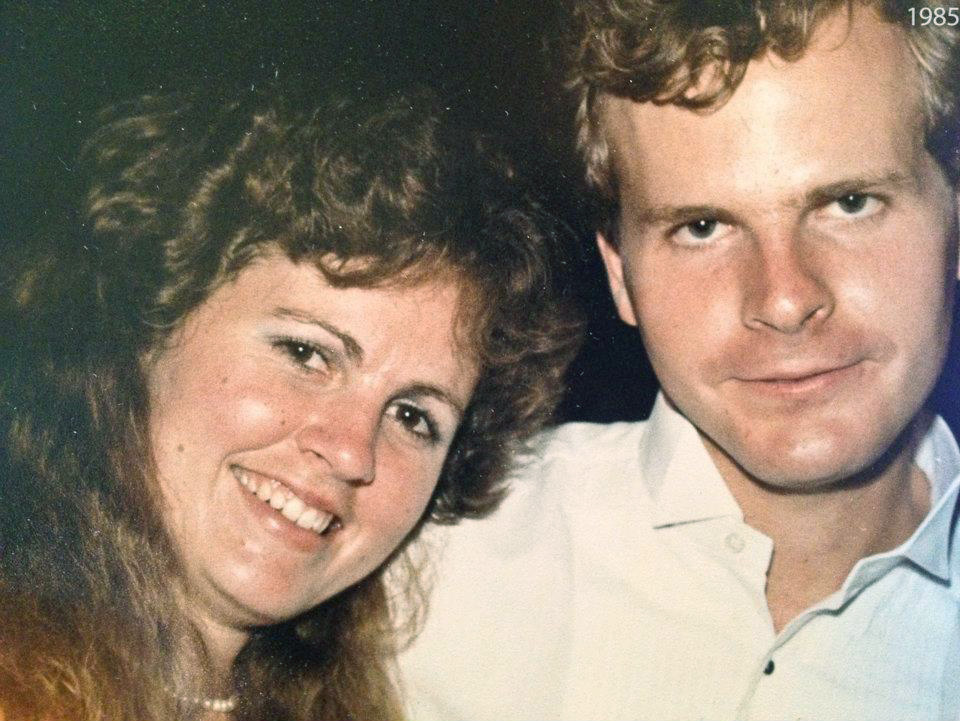

Scott Johnson in Switzerland, 1984. Image courtesy of the Johnson family.

Ten confessed and alleged gay bashers rolled up to give evidence at the Johnson inquest in June. All denied assaulting or killing Johnson. The 27-year-old American mathematics prodigy had come to Australia in 1986 for love – to be with his boyfriend, musicologist Michael Noone – and to complete his PhD at the Australian National University in Canberra.

On the same day Scott’s body was found, police decided it was suicide. Three months later, the first coroner, Derrick Hand, agreed that Scott had jumped. Steve Johnson, Scott’s older brother, didn’t believe it. Nor, initially, did Michael Noone.

It was Noone who, 17 years after the tragedy, contacted Johnson about the possibility of foul play. He had seen the news from an unrelated coronial inquiry and its exploration of attacks upon gay men around the Bondi-Tamarama cliffs. The path around these cliffs skirts Marks Park, which was a very active “gay beat”, a place where men met for casual and often anonymous sex.

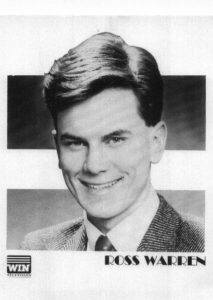

In 2005, Coroner Jacqueline Milledge found that barman John Russell was thrown to his death from a Bondi cliff in November 1989, and that WIN TV news reader Ross Warren – who had vanished without trace four months earlier – was also murdered by person or persons unknown.

Police had originally dismissed both deaths as accidents. Milledge called their efforts “shameful” and “lacklustre”. She found that missing gay Frenchman Gilles Mattaini likely met a similar fate in 1985.

Maybe that’s what happened to Scott, Noone suggested to Steve Johnson. By now Scott’s brother had made his fortune as an IT pioneer, having developed the algorithm that made it possible to deliver pictures over phone lines.

Steve Johnson launched his own investigation. He hired an American investigative journalist, Daniel Glick, who came to Sydney in 2007. On his first visit to North Head, Glick established that the area where Scott died – like Marks Park – had been a gay beat.

This contradicted the explicit advice given to the first coroner by the head of the investigation, Manly’s then detective sergeant Doreen Cruickshank. It was not an area frequented by gay men, she had said. If it was, she reasoned, it would also have been frequented by people who would want to harm or rob the gay men, so police would have known. Police now accept Cruickshank, Australia’s longest-serving policewoman when she retired last year, got it wrong.

Glick surmised that gay men went to gay beats and took off their clothes because they wanted to get lucky, not to commit suicide. Over the next 12 years, the private Johnson investigation triggered a second inquest – which threw out the suicide verdict in favour of an open finding – and now this third inquiry, opened last year and continuing in 2017.

I’m a long-term Bondi local but I came late to this story, in 2013. When I took my infant daughters to Marks Park in the late 1980s and early 90s, and pushed them on the swings, I had no idea what was happening there after dark. I had no clue it was also a playground for gay men and, by extension, for gangs of opportunistic teenagers who came to harass, assault, and even murder them.

I could not have predicted that, in 2015, as a direct result of Johnson’s media campaign, NSW police would launch a review of 88 deaths to consider how many might have been gay-hate murders.

I couldn’t have foreseen my involvement in a documentary screened on SBS last year, Deep Water: The Real Story; nor my difficult discussions with the families of too many dead men, including the Johnsons and the Russells; nor my delicate approaches to the survivors of gay bashings, such as David McMahon.

“Let’s throw him off where we threw the other one off,” McMahon recalls one of his assailants saying. He remembers a gang of up to 18 kids, including girls cheering on the boys, when he was seized in Marks Park on December 21, 1989. He worked in Bondi and knew some of the faces. If they had succeeded in hurling him from the cliff, he would have landed close to where John Russell’s body was found less than four weeks earlier. But McMahon escaped their clutches and ran, literally, for his life.

Three days earlier, and only metres away, three youths confronted Alan Boxsell and demanded to know if he was a “poofter”. He confirmed he was and they bashed him with a skateboard and broke six of his ribs.

Boxsell and McMahon identified a common assailant, a Bondi local, although there’s never been enough evidence to charge him. Boxsell also identified a teenager who was charged and convicted. That didn’t teach him his lesson. Seven months later, the same kid and his brother – armed with a claw hammer – and another teenager went to Marks Park and attacked two gay men. One of them, a Thai national called Krichakorn Rattanajurathaporn, fell to his death from the cliff. The boys were convicted of his murder.

Then, five months later, in December 1990, eight boys found a phone number on the wall of the toilets in inner-city Alexandria Park, another gay beat. They called the number to “bait the poofter”. His name was Richard Johnson, no relation to Scott. He arrived and they punched and kicked and stomped him to death. The ‘Alexandria Eight’ were convicted of murder and manslaughter.

Secret police tapes caught some of them boasting of “fag-bashing” and “cliff-jumping” at Bondi. “Heaps fun,” one gloated. Homicide detective Steve McCann, since retired, defied resistance from colleagues and started joining the dots between a spate of gay-hate attacks.

Ten years later, another homicide detective, Steve Page, was so moved by a letter from Ross Warren’s mother, Kay, that he answered her plea to seek answers to his disappearance. He kept joining the dots. He dared to uncover holes in past police work while he led a three-year investigation, Operation Taradale.

This led not to the conviction of any killers but Milledge’s damning coronial findings in 2005 and, at least, a finding of murder. Page and McCann both worked with Sue Thompson, a lawyer who was the police force’s gay liaison co-ordinator until 2002. On her first day in the job, in 1990, Thompson took a phone call from McCann. He needed her help on the Richard Johnson investigation, which succeeded in putting the ‘Alexandria Eight’ behind bars.

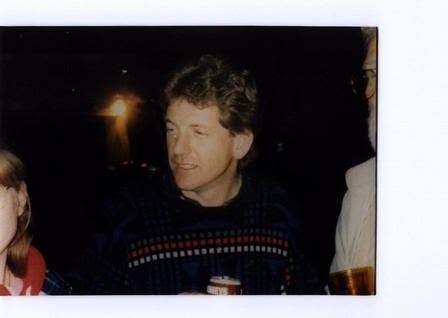

Victim, Ross Warren

The 88 deaths now under review by the police force’s Operation Parrabell are drawn from lists compiled by Sue Thompson and criminologist Stephen Tomsen. Parrabell is yet to report because it is currently the subject of an independent academic review, but the force’s Unsolved Homicide team is highly sceptical about the number of cases that might be gay-hate murders.

Thompson and Tomsen, in turn, believe Parrabell has adopted an FBI methodology for “bias crimes” that is not fit for the purpose of assessing these cases. Among the 88 are 30 unsolved deaths, which Thompson and Tomsen have since honed to 22 that they consider most compelling. The force has so far accepted only eight as probable or possible gay-hate crimes. Scott Johnson is not among them.

Detective Chief Inspector Pamela Young, of the Unsolved Homicide team, spent about two years leading Strike Force Macnamir, a re-investigation of Scott’s death. Her conclusions, contained in a 439-page report to State Coroner Michael Barnes, give most weight to the original police theory: suicide.

Michael Noone, the boyfriend, disclosed that Scott – as long as four years before his death – had written him a letter, which he says he has since lost. Scott had written that he wanted to “do away with myself”. He had told Noone about a sexual adventure in America and his fear, unfounded as it turned out, that he had contracted HIV. Scott had gone to the Golden Gate Bridge wanting to jump to his death but “his muscles froze over”, and he couldn’t proceed, Noone told the inquest last month. By the time Scott died, Noone was convinced he had put any thoughts of suicide behind him. “He was flourishing,” Noone told the inquest.

On the last day anyone has reported seeing Scott alive, two days before his body was found, Professor Ross Street assured him that a mathematical solution he had reached in number theory would secure his PhD. Scott arranged to meet Street the next week.

But Noone has wrestled with the possible causes of Scott’s death. Did he fall? Did he jump? Or was he pushed, chased or frightened off the cliff?

Last month, Noone described a painfully shy young man. He also spoke of Scott’s “spiral of self-blame” and “depression” over another infidelity in the months before his death. Noone told DCI Young’s investigation in 2013: “You can have an accident at a beat. You can suicide at a beat… You can go there seeking sex with somebody and be so full with remorse afterwards, or disgust, that you can then suicide… these all seem to me to be possible explanations.”

Noone spoke, too, of Scott’s deep interest in Alan Turing, the British computer theory pioneer and leader among World War II codebreakers. Turing was prosecuted for homosexual acts in 1952 and in 1954 he died of cyanide poisoning, a suspected suicide.

“It’s just rubbish,” said John Agius, SC, counsel for the Johnson family. He said that to liken Scott with Turing – whose “name was trashed”, who was outed for a then illegal act, and who was declared mentally defective – was “so far-fetched” that the evidence should be struck from consideration.

Two expert witnesses, a psychiatrist and a forensic psychologist, told the coroner that suicide could not be ruled out, but both did not believe Scott set out for North Head with a plan to kill himself. Both also placed little weight on his past suicidal thoughts as reported. Psychiatric nurse Walter Grealy had given evidence last year of an “odd” remark Scott made to him at a party – seven days before his body was found – that he had twice thought about jumping from a bridge, including once in Sydney. Grealy regarded it as an attention-seeking or “historical thing”, not an expression of suicidal intent. Again, the psychiatric expert Matthew Large told the court, “I don’t give it much weight”. He saw nothing to indicate suicide was likely.

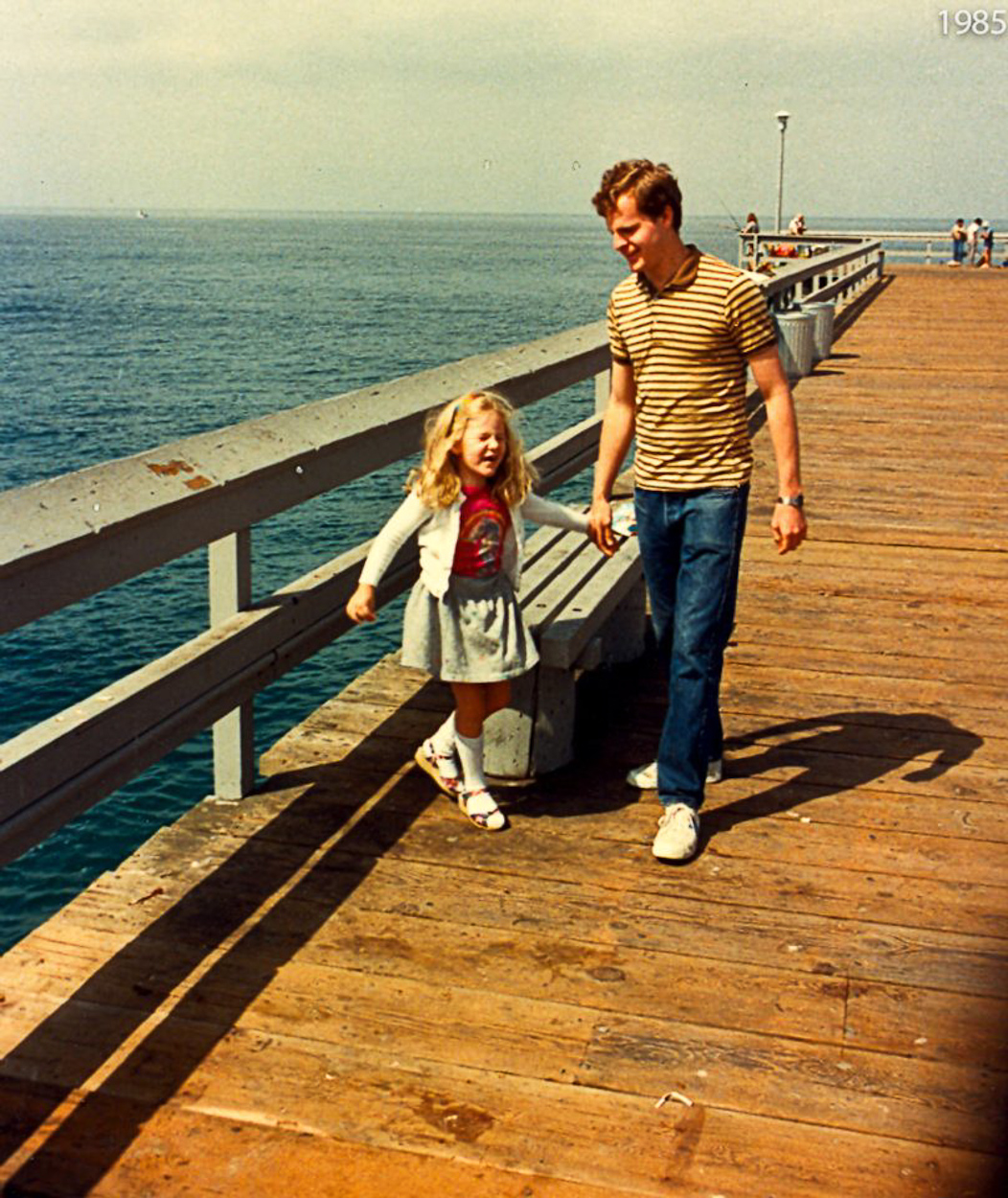

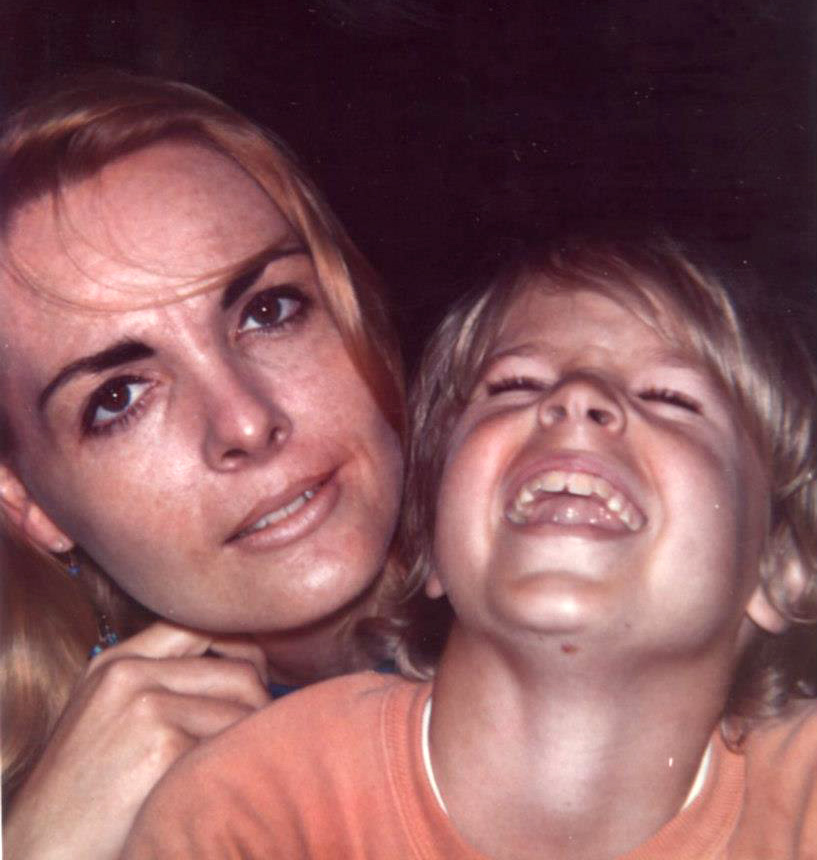

Scott Johnson’s partner Michael Noone, 1988.

Michael Noone is a musicologist and choral director at Boston College. Steve Johnson also lives in Boston, but they are no longer talking. Noone stopped answering emails in 2011, “sick to death” of accusations that he had hidden information relevant to Scott’s case, he told police in his lengthy 2013 interview, which is presented in Young’s report to the Coroner.

The tensions go back to their first encounter, according to Noone. He told the inquest that Scott was extremely close to Steve but coming out to his brother as gay had been “fraught” – a claim rejected by Johnson. Noone said Scott was deeply hurt in 1985 when they arrived in the US to be told they were not welcome to stay together at Steve and his wife Rose’s unit. “He said one or other of us would be welcome but not the two of us, and Rose said, ‘I’m not having any of that in my house.’”

Johnson has disputed this account, too, saying Scott and Noone could not both stay simply because their home unit was so small.

DCI Young had her own bitter tensions with Johnson. On the day State Coroner Barnes announced the third inquest in April 2015, Young gave a very frank interview to the ABC’s Lateline. She talked up the evidence for suicide. She also claimed former police minister Mike Gallacher had “kowtowed” to the Johnsons and put “improper”pressure on police to give them priority ahead of hundreds of other families awaiting answers about loved ones. Gallacher, a former cop, vehemently rejected the accusation, while the Johnsons said Scott’s case – unlike many cold cases – had never previously been “investigated”.

Within days, Young was removed from the case after Barnes declared her interview had undermined public confidence in her impartiality. When asked on Lateline if the original police investigation had been flawed, Young said: “Not at all. It was to the standard of the day.”

The State Coroner doesn’t seem to agree. Barnes is yet to make his conclusions, and his counsel assisting, Kristina Stern, SC, made clear from the outset that this inquest is not to be an inquiry into police failures. Nevertheless, towards the end of his nine days of hearings in June, Barnes said he understood the Johnson family would be “puzzled and dismayed by the paucity of the original investigation”.

Barnes made this remark while announcing he would not require the original Manly detective, Doreen Cruickshank, to give evidence. He was satisfied that deaths were not properly investigated near places where men met for sex in the 1980s, 1990s and more recently. However, while the Johnson case was “clearly based on less evidence” than is now available, Barnes said there was nothing to suggest police deliberately suppressed information.

Cruickshank, who rose to North Shore commander and was widely honoured when she retired after 45 years last year, did not respond to a request for comment. She is the one who told the first coroner there must not have been a meeting place for gay men on North Head because, if there was, gay bashers and thieves would also have attended.

DCI Young’s report argues differently: Yes, it was a gay beat, but it was a beat devoid of gay bashers. Neither Young nor the police force are at liberty to respond to Barnes’s criticisms while his inquest continues, but her statement to the State Coroner noted the “total absence” of reports of violence targeting gay men to either the police or the public hospital on North Head at the time, and the failure of a single person to come forward despite a flood of publicity in recent years.

“Based on these realities,” Young wrote, “it is not unreasonable to draw an inference that no crimes of personal violence occurred at the North Head gay beat, and certainly none that required medical treatment”.

But gay bashers did attend this beat, according to Gordon Sharp. He was among another procession of witnesses at the inquest last month – the North Head beat users.

In colourful testimony, they described passing through a hole in the old sandstone wall above the Shelly Beach car park. From there they’d negotiate a maze of “goat tracks” through the scrub on the headland. There would be men like “rabbits bouncing around”, one witness said. They might go cruising for company, said Ulo Klemmer, or they’d take off their clothes and sunbake and “wait for someone to approach”. Sharp recalled: “You’d see a head bob up. Hello, I like that head. I want to go and check out the body.”

“Being Sydney,” Sharp explained, “that particular beat is like Sydney real estate. Position, position, position. Everyone seemed to have their own rock area and the most prominent position was occupied by a man called Fred Tumbridge… And he seemed to have title over that rock.”

Sharp knew it as Tumbridge Towers, but he used the beat between 1967 and 1976, more than 10 years before Scott’s death. Later users called it the Fairy Bower beat. While he never witnessed a bashing, “Occasionally the word would go up – basher!”, and he spoke to victims later at the nearby gay bar at the Manly Pacific Hotel. “Come that evening, you would find someone at the Silver Dollar Bar who’d had a smacking around the head.”

Did they report the attacks to police? “No one saw the value of reporting to the police because you were likely to get another smacking from the police.” The mistrust of police and the refusal to report assaults was a persistent theme among the gay witnesses.

Sharp’s friend Bryan ‘Sadie’ Tompson was stabbed by a man with whom he had sex at the beat in 1986. In her report, Young cites this attack as the only known act of violence in the beat area, but she rejects it as crime with a gay-hate motive. In any case, Sharp told the court that his friend, now dead, had kept using the beat until six to eight years ago. “Nothing on this earth would stop Bryan Tompson going to a beat he liked.”

The ’70s, ’80s and even early ’90s were very different times. Sex between consenting men was still a crime in NSW until 1984. It was 1997 before Tasmania decriminalised gay sex. Until the law changed, NSW police could prosecute men for the “abominable crime of buggery”. After the law changed, some police persisted in harassing men at gay beats. Former officers have told me of “hoodlum patrols” that would go to the beats to give gays a hiding. They’d go “spotlighting” to find the men, like rabbits, in the bushes.

Why would gay men expose themselves to such risk? There were no mobile phones, no internet, no dating apps – no Grindr or Tinder or OkCupid – with which they could arrange liaisons. They had the beats: enticing, exciting and sometimes dangerous. The law reforms emboldened them in their age of sexual discovery. Many closeted gays came out, loud and proud. Many married men enjoyed the anonymity of the beats.

The 1980s also brought HIV and AIDS – then a death sentence. With that tragedy came hysteria, and a backlash against gays. “Those ads have a lot to answer for,” Steve Page, the former homicide detective, told me in 2013. He was referring to the 1987 AIDS-awareness television campaign in which The Grim Reaper used a bowling ball to skittle men, women and children, regardless of whether they were gay or straight. Blamelessly straight was the message for some viewers. For too many it left an unintended impression: The Grim Reaper was a poofter.

The tattooed man who took off his shirt in court insisted the Reaper on his arm was unrelated to the small-screen television version or his attitude to gay men. Another of the Narrabeen bashers, however, admitted he had a “bad attitude” and he volunteered: “It was probably because of the ads on TV.”

He admitted he was one of the Narrabeen skinheads. He was 16 when he and his mates bashed a man in Moore Park.

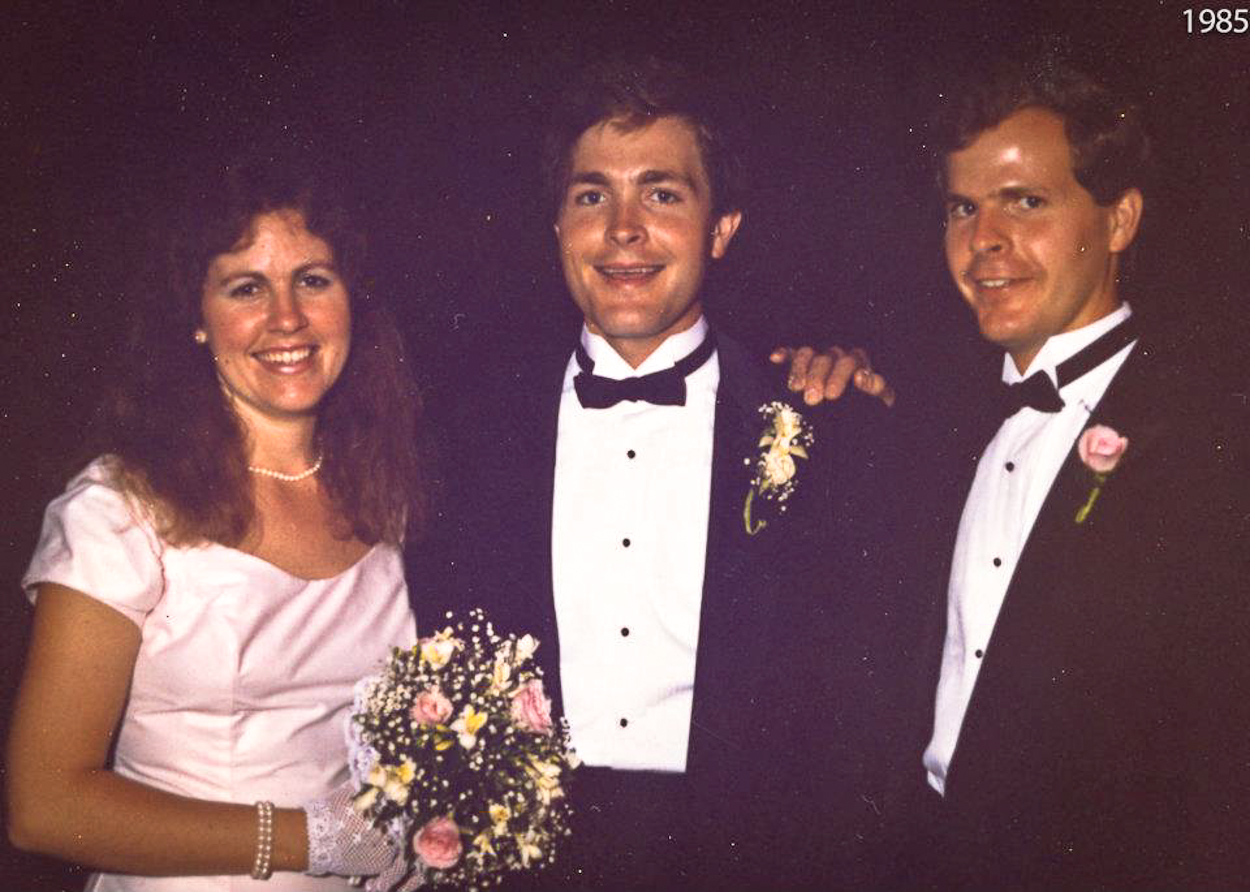

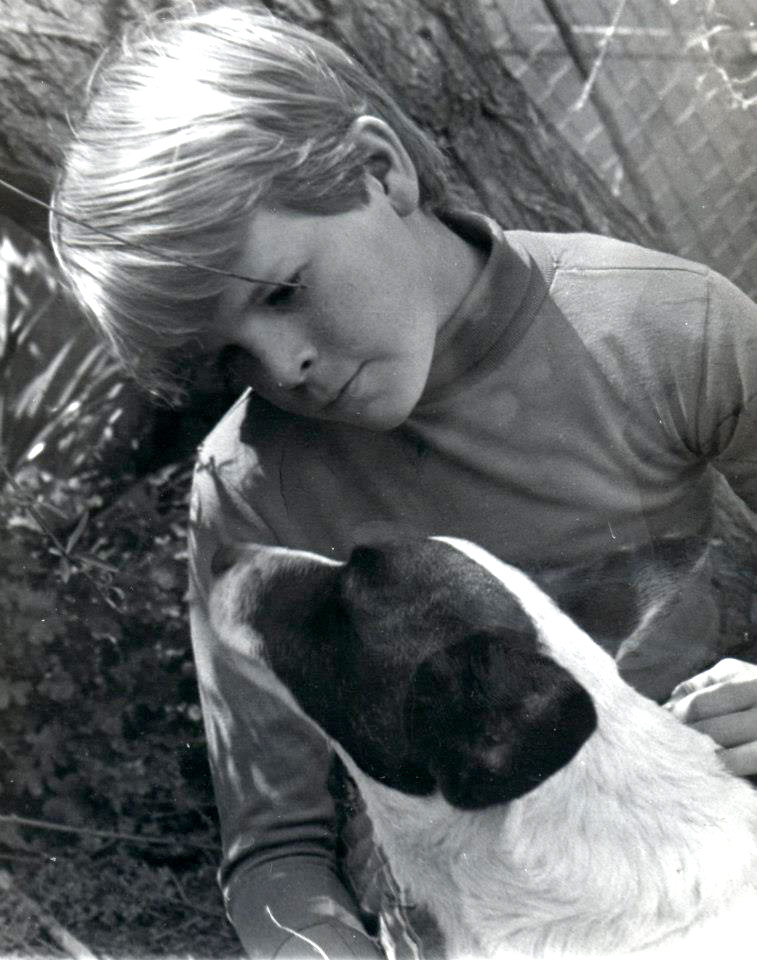

Scott in the mountains, 1987. Image courtesy of the Johnson family.

Another Narrabeen basher was himself a “poofter”. He had been married but told the inquest he went to beats for sex with men at the time. Nevertheless, he was prosecuted along with three teenage offenders for bashing gay men in 1986. “If you were gay yourself, why did you do that?” Kristina Stern, SC, the counsel assisting the inquest, asked. The man, however, now admitted only driving the bashers to the beats. He insisted he never joined in the assaults, although his co-offenders told the inquest he did share in the violence. Stern asked him: “Did you do it to hide your homosexuality?” “No,” he told her.

One of his co-offenders confirmed some of the 1986 assaults at the inquest, but he alleged two corrupt policemen beat confessions out of him for other gay attacks. He denied paying the same policemen a $50,000 bribe to get lighter treatment, and yet he confirmed one of them, Ray Peattie, if not both officers, had attended his wedding.

Peattie was jailed in 2002 for corruption. I put all the claims aired at the inquest to him. “I’ve got one word for you, mate,” Peattie said. “Bullshit. That’s all I want to say.”

The same gay basher, according to evidence given to police by a community witness in 2013, was among a gang that sometimes went to the North Head beat. A member of this gang would act as the “bait”, attracting homosexuals for his mates to bash. At the inquest, the community witness backtracked on some of his evidence, saying the gang had operated at either Reef Beach or at a part of North Head separate to the area he showed police. The gay basher – the one who accused police of beating him – confirmed that one of his gang would indeed act as the bait, but he denied ever assaulting anyone at North Head. How he could be so sure? “I can’t be sure, no. But I say no.”

An apology of sorts came from the man who reckoned he was a “sheep” – just a naive follower, he kept telling us. “There were so many people who did it … gangs on the Northern Beaches.” He couldn’t recall telling police the reason for his assaults: “Just to give the homosexuals a good hiding.” His memory was so vague that the coroner warned he could be jailed for perjury. But he insisted he had learnt his lesson: “They say, to be old and wise you’ve got to be young and stupid.” Kristina Stern, SC, inquired: “What are you sorry about?” He struggled: “Nothing, just sorry.” As a kid he had told police that homosexuals made him feel sick, but now he questioned whether he ever would have said such a thing.

It made me think of Ted and Pete Russell, father and brother of John, the gay man thrown from the cliff at Bondi. In Deep Water, Pete despairs that John’s money and cigarettes were found beside his body. “So they didn’t even steal his fuckin’ cigarettes, you know? What? Why the fucking hell do you throw someone over a cliff? For what?”

There can be no adequate answer, but I’m yet to hear one that goes close. “One in, all in,” an old basher told me last year. He was 12 when he joined the fray on the Bondi promenade, then went home and “bawled my eyes out”. I spoke to the estranged wife of a 1980s teenage basher who wasn’t sorry at all. She reckoned he’d do it again today.

The most frank testimony from the 10 convicted and alleged bashers at Glebe appeared to come from the only one among them who had been found guilty of killing a gay man. “My actions caused someone to die,” he said. “I was wild. I was angry. I was just a very maladjusted young kid.” But why had he thought so little of homosexuals? They were weak. They weren’t manly. “That was my world view. That was my core belief as a teenage boy.”

Steve Page has always wondered if the wider society in the 1980s and ’90s did not care enough about the crimes against gay men, and he has questioned whether some of the poor police work by his colleagues would have been tolerated for any other category of citizen – teachers, doctors, mothers, children – had they been targeted by young gangs and assaulted, murdered or hurled from cliffs.

While the State Coroner considers whether or not that was Scott Johnson’s fate, another community witness at his inquest made a heartfelt confession. He had come forward to testify about his direct contact, as a young man, with footballers and soldiers from the artillery training school on North Head who boasted about bashing gays.

At the Steyne Hotel in Manly in about 1986, he recalled, five soldiers were toasting a milestone for two men in their party. “They managed to catch their first queers today,” one of the soldiers told our witness. The informant had lived near North Head and knew of the beat, so he assumed that was where the soldiers had found their “queers”. He recalled that one of the two debutant gay bashers had a grazed and bloodied fist. “I guess they regarded it as bragging rights.”

If his rough memory of the date serves him well, Scott Johnson could not have been among their victims. But why didn’t he or his friends report the men to police?

“As horrible as it sounds,” he told the court, “we were young and we thought it enough that we weren’t part of it… To our great shame, we just basically let it happen.”

Scott Johnson in America, 1988. Image courtesy of the Johnson family.