“I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their neighbourhoods,” states Truman Capote’s unnamed narrator in the opening pages of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. This seems an appropriate way to begin a love story, as there is a kind of romance to lingering on the doorstep of places where one used to live.

It’s like crossing paths with a lover from long ago – you still have these memories, but you can no longer access them. All traces of your touch have been painted over, the locks have been changed, the intimate turned foreign. And perhaps someone else is living there now, walking around in your what-could-have-been, making their own marks.

What are our cities and landscapes if not maps of memory and erasure – especially in Australia, where the original stories of the land have been written over, the narrative reframed. In walking the streets of our old neighbourhoods this becomes clear, as we see the double-exposure of the present and what we remember. Every house of the past is a haunted one.

For the first eight years of my life, I moved house once a year, sometimes twice, if both my mother and father decided to relocate. There is no single place that contains my childhood, but I can trace my early memories along the City Rail map of the Inner West line. Since they moved to Sydney – separately – when I was four, my parents continued to orbit one another across a series of inner-city suburbs.

My mother bought houses by railway lines on the outer-edges; my father shuffled in and out of rented homes. I learned to ground my memories in these places and track time through location. When I remember the warehouse in Newtown where I once watched a stranger’s hand reach between the bars of our open front window on Wilson Street and feel around blindly for something to steal, I know I must have been six, because my father lived there for one year in 1996. That year, my bedroom was up a spiral staircase in the former attic, and the sloped A-frame walls meant he had to stoop when he tucked me in at night. No matter what shape our rented houses took—a terrace or a bungalow or a flat above a shop – I learned that home was temporary, but the sense of it could be carried with you and re-made.

176 Parramatta Road was on the border of two suburbs. We lived on the Stanmore side, but across the four lanes of traffic was Annandale, a suburb of leafy streets and turreted houses I always imagined to be filled with ghosts and witches.

My father and his then-partner bought the property twenty years ago – it was the first and only place they’d own together – and the three of us moved in at the beginning of 1998. When I think of that house now, I picture its curious structure – what looked like a two-storey shop-front with an apartment above it was really two separate buildings, the top floors linked by an external wooden bridge. Below, an avocado tree grew out of the courtyard, its branches curving around the middle of the walkway, and in the six years we lived there it yielded only one black fruit. In memory, the place looks something like a child’s version of a castle – long and lopsided, rooms perched high above the traffic, the bridge in the middle sheltered by green leaves.

We painted the house in crazy colours. The outside of our shop, which would become Silicon Pulp, a short-lived animation gallery directed by my father and stepmother, was coated in pearlescent teal and deep purple. It is a different place now – long ago the sliding doors were replaced, the façade repainted in a neutral scheme, the gallery turned into the kitchen for a takeaway noodle shop. Still, of all the places I have lived, it’s the only place which remembers me and on which I’ve left a permanent mark: my childhood nickname, carved in wet cement by my father’s hand in the alleyway behind our house.

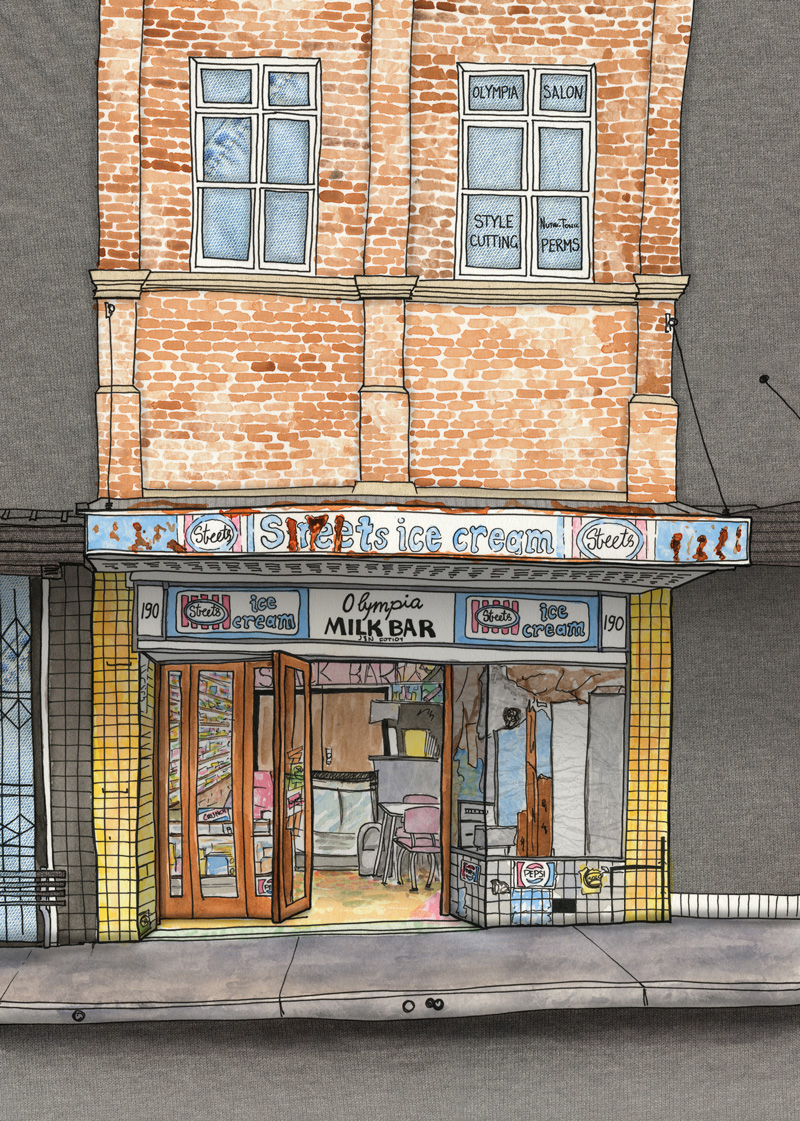

Olympia Milk Bar on Parramatta Road

Parramatta Road is notorious in Sydney for being the clogged artery that connects the Western suburbs to the heart of the city, a transitional space of car washes and dealerships and fast food restaurants, but for six years I called a part of it home. In 1998 our strip was white creampuff off-the-rack wedding dress shops next to the red-dressed windows of brothels named only by the building number, a Shell petrol station opposite an Italian motor scooter dealer, a discount retailer for stockings, a wine store and a bank and a newsagency, a Franklins that became an IGA, and an old sandwich shop that sold hot chips wrapped in butchers paper and sprinkled with vinegar. We lived in the same block as the Stanmore Twin, a picture theatre locals called “The Globe” that played double features on Sundays, and just a few doors down from the iconic Olympia Milkbar.

While the cinema was razed in 2000 to make way for new apartments, the Olympia outlived most businesses on that strip until last week, when it was forced to close by the Inner West Council until extensive repairs are made to the crumbling foundations. Since the shop has existed in a state of increasing disrepair as long as I can remember, these renovations seem unlikely.

From the outside, the milkbar always appeared abandoned. Inside, it was like a decaying museum of another era. It could have been the last diner on earth, complete with decades-old, peeling Formica tables and a greasy metal countertop. Dust and grime from Parramatta Road had faded the original art Deco design that spelled out OLYMPIA in the terrazzo floor, and down the back, beneath the single bulb that was used to light the place only at night, a burned-out neon sign read: “Late suppers, steak, sandwiches, snack bar.” From the run-down exterior many passersby would assume the shop was closed if they weren’t familiar with the myths that surrounded it.

Every childhood deserves a Boo Radley house and the Olympia Milkbar was mine, although I didn’t realize it even had a name until years later when I recognised a description of the place in one of Vanessa Berry’s early zines. My family called it, somewhat affectionately, “Zombie’s,” after the strange and reticent owner. With his grey pallor, black eyes and white hair, he looked undead or at least well over one hundred in my child eyes, though he would have only been in his sixties at the time.

Over the years, we imagined him, variously, as a living ghost or a vampire, for the way he seemed to materialise out of the dark while you stood waiting at the counter, only to realise he’d been lurking in the shadows the entire time. He seemed to float an inch above the floor, and I never remember him speaking except in a low, creaking groan. Another friend of mine who grew up in Annandale remembers the Olympia as “The Dark Place” where her and her brother bought candy bars that turned to dust in their mouths. On extensive Reddit forums and Facebook groups, I’ve seen it referred to by others as “The Haunted Milkbar,” the owner nicknamed “Drac” or “Dr. Death”.

Little is known about Nicholas Fotiou, who is still notoriously private, except that he was part of a generation of Greek immigrants who bought American soda pop culture to Australia in the more wholesome and calcium-rich form of the milkbar. According to historical records reported in the Sydney Morning Herald, he emigrated from the island of Lemnos in the 1950s and purchased The Olympia with his late brother John, who died in the 1980s. In one version of the story, the shop was preserved as it was then, in memory of the lost sibling. Another version speaks of a feud between the brothers, the business left open but never maintained in an act of bitterness and spite.

Other rumours persisted. The Olympia kept strangely long hours for a place that seemed to have so few customers – possibly a hangover from the days when it was connected to the movie theatre by a window cut into the wall—and this lead to speculation the milkbar actually served as a drug-front. There were whispers of a wife who used to run a hair salon above the shop, of children who had died in an accident. Over the years, gothic scenarios were invented, The Olympia becoming the imaginary setting for something like an Inner West version of Faulkner’s ‘A Rose for Emily’, featuring the decaying corpse of a mother or bride hidden away upstairs.

My friends and I thought up more childish stories about how the owner slept in a crypt and roamed the neighbourhood late at night, and dared each other to peek over the back fence in Corunna Lane to see what bones or relics he might be keeping in his yard. If this seems cruel, I hadn’t yet learned the lesson of Boo Radley – that these characters we conjure out of figures from our childhood are actually just people, and perhaps they would tell different stories about themselves if given the chance.

Parramatta Road has always existed in a state of flux, and the history of the Olympia Milkbar dates back to the development of commercial and leisure activity along the strip. In 1912, the building functioned as a billiard room associated with the skating-rink next door, which became the picture theatre in 1939 as recreational culture began to change. Before that, the area was known as Annandale Farm – 100 acres stolen from the original owners of the land, the Cadigal and Wangal clans of the coastal Eora people, and claimed by Captain George Johnston in 1793 who tried to graft English pastoralism onto Aboriginal land.

During the years The Globe was open, The Olympia functioned as a kind of candy bar annex, where people would go for milkshakes before the show. Inside it was always cool, dark and dusty, but after the cinema closed, it gradually grew more decrepit. I waited for the bus outside the store and by the time I was in high school, one of the shop windows was permanently broken, cutting a jagged shape that was only sometimes taped over with paper.

Since my father worked with stained glass during his day job making leadlight windows, he offered to repair the damage as a gesture of goodwill but his generosity was rebuked. We had always assumed the owner was poor and struggling to turn a profit since the movie theatre had shut down, and were surprised to learn later that he owned many other properties in the neighbourhood.

Even though we lived across from a supermarket and down the block from a 24-hour petrol station, my father and I often went into the Olympia to buy our after dinner treat. I remember blocks of dark Old Gold, mottled with white from where the chocolate had melted and re-set. For a long time I thought this was my father’s way of trying to keep the shop in business. It never occurred to me that the Olympia was a crumbling relic of his own boyhood growing up further down Parramatta Road in Ashfield in a small house with his mother, sister, grandparents, uncle and aunt all under one roof. My father would visit the milkbar after school as a student of Fort Street Boys, until he was kicked out for, among other things, having hair that was too long. Even back then, the business was beginning its slow decline.

The name Olympia refers to the mountain Olympus, the home of the gods in ancient mythology. In Greek, too, one can find the etymological root of nostalgia, the feeling I’ve been trying to describe. It originated from two separate words: Algia, pain, and nostos, return home.

Though it was twenty years ago that my family moved into the house on Parramatta Road and painted the front a seasick combination of purple and teal and since then I have lived in many other places that I’ve come to call home, crossed oceans, married, it is the closing of the Olympia that feels like the final curtain call on my childhood. All that remains is my name in cement. The rest is dust.