Rayyane Tabet, one of the stars of the 21st Biennale, has placed himself in the most obvious and overwhelming of locations. The Sydney Opera House and, more specifically, the Utzon Room, reputedly the only space completed to the visionary architect’s original specifications.

It’s hard to know what to call Tabet’s work: a performance monologue, an installation of found objects, an historical detective story, a love letter, a séance?

Entitled Dear Mr Utzon it is all those things. Truths gathered in fragments. A collection of objects drawn from around the Opera House and associated archives that tell us something new about a building we think we know.

Tabet himself is something of a human collage, born in Lebanon, educated at the American University in Beirut and now resident in the USA. Trained in architecture, he completed degrees in cultural studies at institutions in New York and San Diego, focusing on post-conceptual art and minimalist traditions. One can see these influences in his sculptures and installations, though Tabet admits, “I failed my theory classes because I preferred fiction. I love short stories. Their intense descriptions of a scene, place or character and how that conjures up a form in your imagination.”

The truth is that although much of Tabet’s work is sculptural and installation based, “it has been about showing the sensibility between an object and a story” and “creating environments where stories can be shared”. After refusing the Biennale’s initial invitation, he found himself seduced by the taken-for-granted objects and submerged stories within the Opera House.

One of the more startling involved the 1960 murder of an 8-year-old Bondi boy called Graeme Thorne. Kidnapped after his parents won one of the early lotteries used to fund the building, he was suffocated by his abductor. Tabet explains “this was the first conviction to make use of forensic science in Australia”.

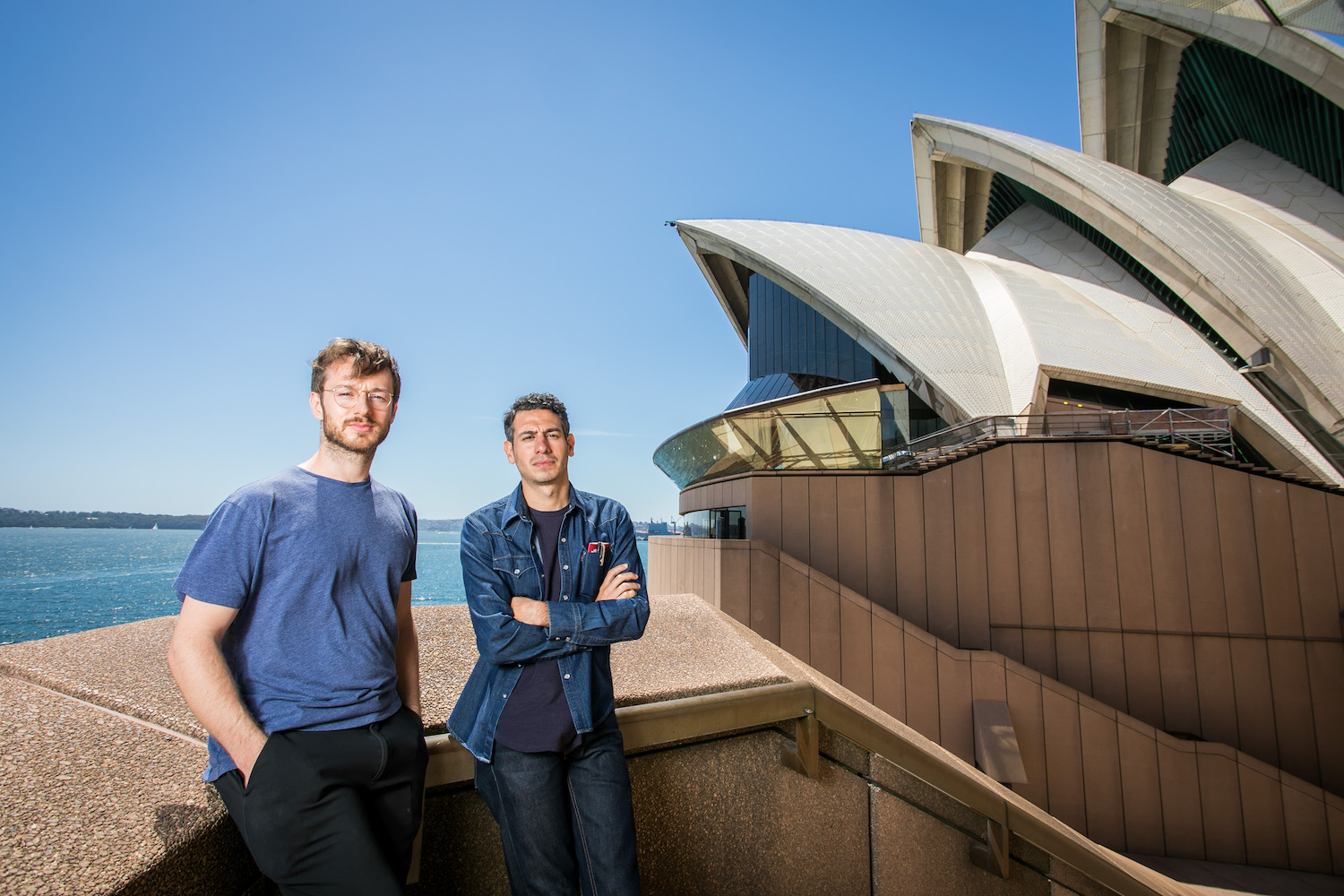

Sydney Biennale artists Oliver Beer and Rayyane Tabet (right) at the Opera House. Photography by Anna Kucera

We drift to talking about the writers and short stories that Tabet admires. Ryszard Kapuscinski and his myth-making non-fiction. Paul Auster’s uneasy games of identity and confession, where protagonists find the familiar breaking down. The meta story-telling of Roberto Bolaño with its grit and darkness. The essays of Alexander Kluge that take on a fictive tone. Classic works like James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ and its mood of predestination and sorrow.

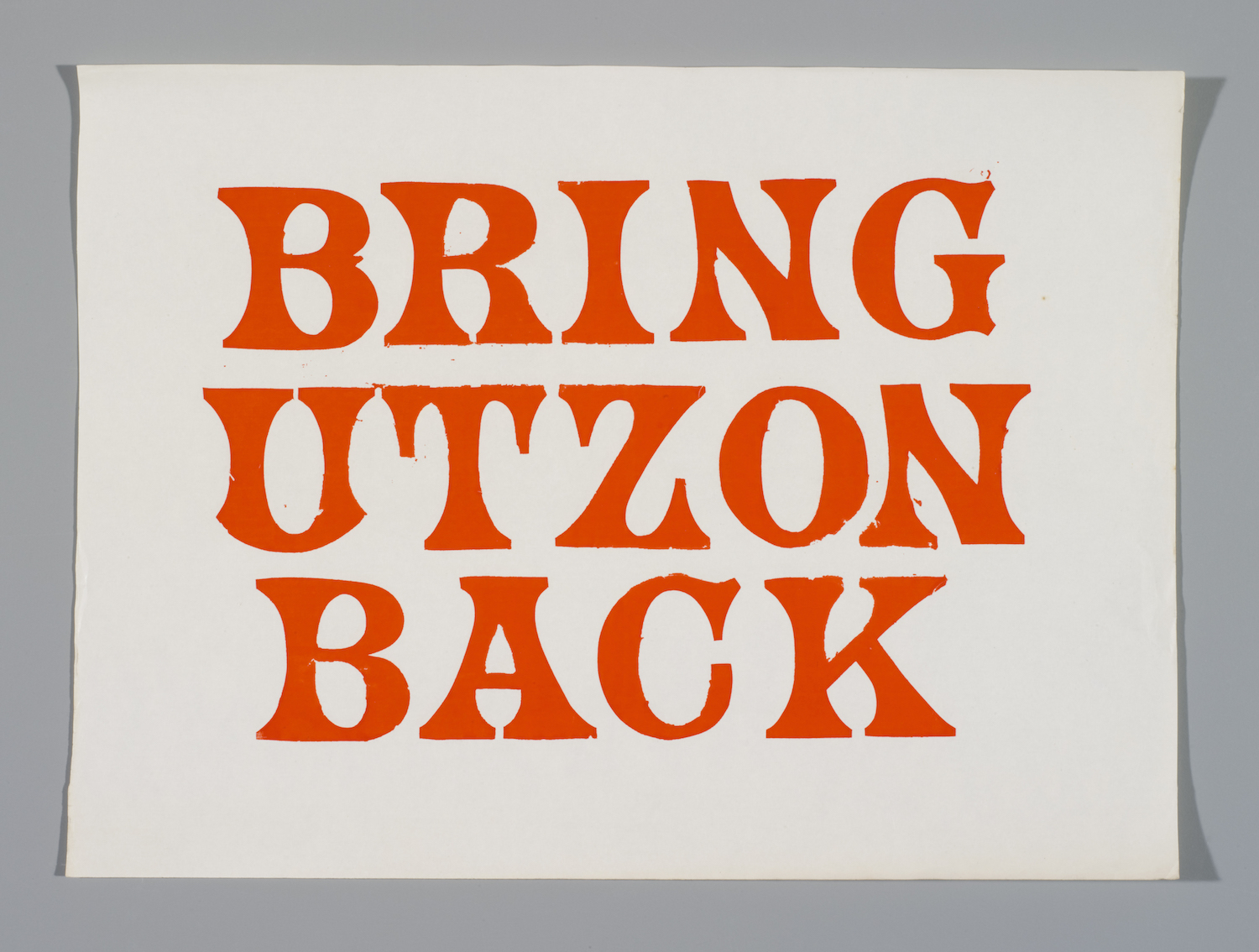

By 1966, architect Jorn Utzon was being dismissed and, as Tabet puts it, “being sent into exile”. His extraordinary designs for the internal structure of the Opera House would be overridden by more clumsy politics and practicalities. For such an organically brilliant design this was a real disaster, one that would plague the Opera House for decades to come with the common complaint that it was the best-looking worst-sounding opera and music venue in the world. Utzon himself suffered too as great artists do when a major work is blighted and frustrated.

In some strange overlap of mutual biographies, Tabet says he found out about another frustrated Utzon plan. “His first project after the Opera House was meant to be a theatre that was to be built inside a cave in Lebanon. Not many people know about this. The cave was narrow, hard to get into. So this theatre was to be built as a procession of pieces, modular elements brought in one by one. The idea was that all you then needed was to put a fire at the centre and have people gather round and tell their stories.” It never happened.

Tabet felt an obligation to complete a story of some kind sown into such events. He noticed a tapestry by Le Corbusier, now hanging at the Opera House, in a photo that originally showed it in Jorn Utzon’s home in Denmark. He was fascinated to discover correspondence between Le Corbusier, then a legend, and the young, relatively unknown Utzon. With Utzon, in a mix of admiration and assertiveness, sending off letters to one of his architectural masters importuning him to advise and contribute in the way that Utzon wanted. And Le Corbusier responding to the young genius.

“Next April is the 100th anniversary of Utzon’s birth,” Tabet says. “It was reading the letters, the strength of his voice, when I realized I wanted to write a letter to him and tell him these stories that I was discovering.”

In writing Dear Mr Utzon, Tabet began to understand that all of this was, for him, “about how failure is as necessary as success”. He meanwhile denies that he is by nature a nostalgic artist himself, always digging into the past through objects. “It’s more a way to understand the conditions that I find myself in today. Grand historical narratives are usually written through grand historical events. They can seem impenetrable. But there are these moments where you can insert yourself back into history – and make it your own.”

“So, in a way I can find that I exist within this building,” he says, laughing lightly. “At the same time even its own maker cannot find himself within it.”

Tabet believes the Opera House has “many personal, tragic moments that make the building more brittle and complicated, more tragic in a Greek way”. In piecing together newspapers, lamps, furniture, paintings, leaflets, he presents us with an archeological ghost story, shadows cast on a white cave wall.

Rayyane Tabet, Dear Mr Utzon, Sydney Opera House. Monday 19 March (4pm & 7pm); Tuesday 20 March (1pm, 4pm & 7pm)